Big Timber: Where would we be without it?

Words Lester Perry

Image Cameron Mackenzie

Once upon a time, Aotearoa was covered mainly by a blanket of native bush. You know the stuff? It’s what most mountain bikers love to ride: large trunks, matts of roots dispersed with fertile dirt, and leaf litter (Beech leaves if you’re lucky).

And this bush was the habitat of many native NZ species. Early Maori cleared what land they needed for agriculture and living space, but it wasn’t until European settlers came ashore in the early 1800s that the axes really got swinging. In the space of roughly 200 years, we (humans as a whole) have cleared a fair chunk of NZ’s land mass, leaving just 24% of it covered in native bush. Forty percent of this lump of land we call home is now pastoral farmland, and 6% is commercial forest, which is also home to a large percentage of NZ’s mountain bike trails. As sustainable as commercial forestry operations now aim to be, there’s no denying that this – combined with pastoral farming – has altered NZ’s ecosystem permanently.

While driving the black band of road that dissects farmland throughout this fine country, I often wonder: what would NZ be like if it were still fully forested and, more specifically, what would mountain biking be like if it were?

Anyone who’s spent time on the end of a spade digging a trail in the native bush would agree it’s hard graft, and working the earth through native bush with a digger is a chore requiring time-consuming finesse and, unless you’re comfortable destroying native roots and eco- systems, then it’s all but impossible. With diggers off the trail builder’s menu when they’re working in native, the speed of trail building would be slow, and the extensive networks we currently see would be a figment of imagination.

If, theoretically, all our trails were in native bush – and given the time necessary to build them by hand – the cost of a build would render them basically out of reach financially, and trail building companies, of which NZ has a number, would be almost non-existent. A lack of professional builders would mean volunteer builds would rule. Lord knows how difficult it is to get a regular crew of keen volunteers to commit to a build under the canopy of pines, let alone the challenges native bush brings.

Native trails are my favourites; their environment and the fact they’re generally hand built give them an inherited technicality and often unique style of flow. It would be amazing to be riding native trails every time we went for a ride. Digger-built flow trails – be gone!

I’m not a hater, though; pine plantation trail networks have enabled NZ’s MTB scene and industry to boom, thanks to their accessible, well-groomed, quickly-built trails. The trail is less directed by the lay of the land or preservation of native trees and more by wherever the digger driver points their machine. With only a small number of roots to dodge, or undergrowth to clear, these trails come easy. On many trails, pine needles help protect the surface through winter and, come spring, a leaf blower and a rake can help rejuvenate much of the trail surface. No one likes losing their favourite trail to logging. Still, with commercial forests running on a 25 – 35 year logging cycle (usually the shorter), it’s inevitable that at some point, one of your favourites will be gone. Once trees are felled, there’s a relatively clean canvas to work on, the opportunity for new trails, and the commercial operations that usually build them. But let’s not forget all the logging slash that’s caused significant problems in the last few years, or that trails built in clear fell generally take much more upkeep and are often terrible to ride due to erosion through a wet winter.

Although I’d love to see a country blanketed in native bush again, I can’t imagine NZ would be such a mountain bike mecca if it was. It’s a little Yin and Yang but, ultimately, big timber will continue to thrive with or without MTB trails. I fear that, without it, the growth and popularity of MTB trails in NZ would be stifled, and we wouldn’t be the global destination we are.

CamelBak H.A.W.G Pro 20

Words Lester Perry

Images Henry Jaine

RRP $299

Distributor Southern Approach

There’s a particular style of trip where bike bags strapped to your frame either aren’t suitable for the route you’re attempting or simply don’t provide enough capacity for the required gear.

When Kieran Bennett and I took on our ‘Starevall or Bust’ two-day mission in the summer of 2024, we had an Aeroe handlebar cradle and dry bag each. That was handy — but with the trail being steep and technical in many places, the option for a rear rack was off the cards, and frame bags would have had to be custom made for our full-suspension rigs (and even then, wouldn’t provide the capacity we needed). CamelBak’s range of Packs was the answer — in my case, the H.A.W.G Pro 20, while Kieran went with a similar, but smaller, MULE Pro 14.

The H.A.W.G pack is designed precisely with missions like ours in mind. Twenty litres capacity, supplied with a 3-litre bladder, and room for another if needed. I opted for a single 3L bladder and a water filter, which, if you’ve read the trip report, you’ll know was a necessity!

Stowage is split into three main areas; nearest to the body is the hydration bladder sleeve. Outside of this, another large ‘full’ pocket features two large internal pockets, one of which is designed to hold a spare eBike battery if you’re that way inclined. In this section, there was enough capacity for me to stow a dry Merino top, a pair of shorts and a couple of freeze-dried meals. A smaller zipped pocket is on the left side of the back panel, down near the waist belt, although I didn’t use it on our trip. It would be ideal for smaller bits you may need to take with you but do not necessarily need easy access to — for example, a wallet or passport.

The next layer out has a medium-sized pocket featuring a couple of smaller zipped mesh pockets to store little items — in my case, tools and spares behind the zips, and some snacks in the main compartment. Across the top, there’s a fleece-lined pocket that is ideal for stowing glasses – and is large enough for goggles.

The outside of the pack features a stretch compartment, ideal for items that you might need quick access to — in my case, a jacket and bag of trail mix, and a First Aid Kit that we fortunately never required. The clips on either side have small hooks to clip helmet straps to for carrying.

Weight is supported on the hips with a sturdy waist belt and, handily, there’s a zipped pocket on each side for quick access to gear when you don’t want to remove the pack to access. There’s a good amount of room in these pockets. I stashed a disposable camera on the left side for quick access and, on the right, I had some lollies, a multi-tool and a tyre plugger.

The H.A.W.G Pro is the first pack I’ve used with the Air Support Pro Back Panel — a 3D mesh back and harness that supports the bulk of the pack, holding it away from your body as much as is feasible, allowing for maximal airflow between the wearer and the pack. Although it’s still noticeably warmer than no pack, thanks to the Air Support back panel, it feels much cooler than some smaller, more traditional packs I’ve used. The back panel provides a level of rigidity to the whole system and, combined with the harness setup (including the sternum strap), secures the entire pack nicely. It’s well supported, even while fully loaded and tackling rough terrain. Thanks to the secure fit and rigidity, the top of the pack works well for resting the bike on while carrying over hike-a-bike sections — something we spent hours doing while hiking up Mt Starveall.

Two straps wrap around the base of the pack and, once cinched down, they help compress the load, helping keep everything in place; handily, they’re long enough to strap on more gear. In my case, I secured my Thermarest Sleeping Mat to the base and saved valuable volume in the pack itself. There’s myriad uses for these simple straps: tent poles, rolled-up jackets, or (most importantly) baguettes — the possibilities are endless.

The pack is supplied with a snazzy little tool roll and, while it’s great in theory, I found I couldn’t get my preferred selection of tools and bits to play nicely with it. The tool roll stayed home while on the Starveall mission, and I brought my small tool bag along.

As far as hydration goes, I can’t fault the 3-litre ‘Crux’ bladder. Although I’m not a super fan of the huge screw top, it does the trick and is long forgotten once it’s tucked safely into the pack. CamelBak redeemed themselves with their market-leading (in my opinion) bite valve and “magnetic tube trap” that keeps the drinking hose nicely secure when not in use, and snaps easily back into place.

The only niggle I’ve found with the H.A.W.G is on the outer stretch compartment. The clips that secure each side and help compress the load are not a traditional bag clip design, I assume, to allow for the helmet hooks. More than once, I had issues getting the clip to close correctly on my first attempt; unless the clips are aligned perfectly, one side can stick out and not be clicked into place correctly. This led to the clips popping open a few times on our trip. It’s annoying but not the end of the world. With some attention, they work fine and are secure when clipped correctly.

When all’s said and done, I’m a big fan of the CamelBak H.A.W.G and its versatility. It’s large enough for an overnighter, and once cinched down, it’s compact and lightweight enough for just a few hours in the backcountry without feeling like you’re carrying a flappy, half empty pack.

Inno Tire Hold HD Rack

Words & Images Cameron Mackenzie

RRP $1249

Distributor Racks NZ

The concept of a platform bike rack is nothing new, with many of today’s mainstay manufacturers producing several different models each.

Whilst common, there’s seems to be a new brand on the block every other month, each offering a bigger, beefier and “better” option than the other guy – and Inno’s no exception. Up until recently, Inno is a brand I’d not heard of, let alone knew was available in the local market, but I quickly took notice when I stumbled upon their latest Tire Hold HD rack, offering what looked to be a significantly sturdier rack than anything else I’d seen thus far.

Bike racks have been a pain point of mine over the last few years – never seeming to get more than two years out of a Yakima rack before it bends, breaks and/or rusts past the point of safe use. Whilst the way I use it – leaving it attached to the back of my truck year-round and lapping the country in search of the perfect MTB photo – may be a hard life for a rack, they’re a tool, and I expect more. I mean, who has the time or strength to be lifting their 25+kg rack on and off the car and into the garage for storage between weekend Woodhill trips?

Inno’s latest offering, the Tire Hold HD rack, steps things up, offering large weight carrying capabilities, a wide range of tyre size compatibility, and a design that removes any frame contact – one which, up until 2015, was unavailable on a rack outside of the US.

Fitting Inno’s rack onto my truck was a relatively straightforward affair, although, it did require a few small mods to make it all play nice. The rack features a little depth stopper that helps hold the hitch in the same place – presumably for easy alignment as you take it in and out – which I had to remove in order to get the pin holes to align. Their locking pin has a moulded plastic handle, but is of such a size that it prevented it from being able to be threaded in. Removing the plastic handle from the bolt (albeit forcefully) sorted the problem, and it now threads in easily utilising the 8mm hex key head.

As my bike quiver has evolved, so too have my requirements for a bike rack, so the idea of a rack built largely out of aluminium, with the ability to carry up to 34kgs per bike, hold strong and handle off-road use held big appeal.

The strength of the rack is clear when looking at the size of the hardware and pivots featured throughout. The main pivot, which allows the rack to fold, features no-play and is actuated by a smooth and easily accessed grab-handle at the further-most end of the rack. Whilst elements of the plastic components used throughout make me a little nervous, the cowling encasing the main pivot is a welcome sight, helping to keep a lot of the nasty road grime and dust away from one of the key parts of this system.

Loading bikes is where this system shines. With the way in which the ratcheting arms work, the arms stay put once extended, allowing for one arm to be set in position, a bike rolled or placed up against said arm, and the last arm folded up and tensioned using one hand.

Unloading requires a little more coordination and the use of both hands. I find you need to pull the arm back towards the centre of your bike to take the pressure off of the ratchet, and have your other hand depress the release switch on the tray. My only gripe with this is that the ratchet mechanism requires you to keep the level pressed in whilst you slide the arm back, at times leading to you ending up in some creative body positions.

The tyre holders/arms feature a hard-plastic cup which acts as the key point of contact against the tyres and needs to be adjusted depending on the size of your wheels. Doing so is straightforward, but isn’t something you’d want to be doing each time you load your bike. As in our case, if you have a mullet-wheeled bike, or ‘his and hers’ with varying wheel sizes, you find yourself placing the bikes on the rack in the same order and orientation each time to avoid any hassle.

Each carrier bolts onto the main arm of the rack using a t-track style system (similar to what you’d find on roof rack type bike carriers), which allows for close to 30cm of fore-aft adjustment. This range of movement in pairing with the ability to place your bike anywhere on the carrier and adjust the balance of the arms to affect its position means the days of bikes mating is all but over.

Where other racks would creak and rattle, Inno’s HD rack hasn’t made a peep. Even with 45kgs of carbon and lithium swinging off the back down rough, corrugated gravel roads and mild 4×4 tracks, the bikes held rock solid and would barely wobble even, as the truck bounced around. Long journeys are much the same – hassle free and without movement.

The Tire Hold HD is designed exclusively around a 2-Inch hitch, so for those using a smaller hitch receiver or a tow ball, you’re out of luck when it comes to running this heavy-duty bit of kit. Inno offer similar models using a lot of the same materials and construction, but only for those whose vehicles don either a 1-1/4” or 2” hitch. For the towballer’s, sadly you’ll be needing to look elsewhere for the time being.

The ability to lock your bikes onto your rack is a feature you tend not to utilise all that often, but is one which you want to be well thought out and reliable when you need it. Unfortunately for the Tire Hold HD rack, the locking solution is the one feature which really lets it down. Their solution to security is a basic double-loop cable which requires being fed through itself on one end, and the other being clamped down by the hitch’s expanding wedge handle. The cable itself is something out of a primary school bike rack and wouldn’t take much to cut through or pull out of the locked handle. With the bike rack loaded, locking the cable in place would require you reach underneath the rack and fiddle around with a small key, realigning the handle on a small spline, and clamping said cable loop in place.

An easy solution would be to buy an aftermarket bike-lock and chain the bikes together, but for $1249, you’d hope they could come up with a better solution – perhaps wheels locks like the ones found on the Rocky Mounts or 1Up models.

My only other peeve of Inno’s rack is the inability to expand the carrying capacity after the fact. The Tire Hold HD is available in a two or four bike model, but neither option can be changed with the purchase or removal of an extension. Having that ability is helpful both ways – being able to shorten it for around town when it’s just you, or being able to take a car full of friends on riding trips, without the need to have two racks sitting in the garage.

Time will tell how well the Inno rack lasts but, for now, I’ll be keeping this one fitted, at least until I need to carry more than two bikes – and will be carrying my own lock.

CamelBak M.U.L.E Pro 14

Words Liam Friary

Images Henry Jaine

RRP $279

Distributor Southern Approach

I’m always scheming or planning an overnight trip, particularly during that time between the clocks springing forward and winding back again (boooo!). How much gear we actually need on a trip, and what we are going to use to carry it, is always a big consideration.

I don’t mind having some weight on my bike, but I always like to try and keep it free to move, so having a decent backpack with enough storage is an absolute must. Extra hydration is also key when pedaling off into the backcountry for hours and days at a time, making a reservoir a must have. For these trips you need to pack ya meals, snacks, layers, jackets, power bank and locator beacon at the very least, along with other essentials.

The M.U.L.E Pro 14 is aimed at big days out and comes with loads of genuinely useful storage arrays. The back panel is most excellently called ‘Air Support’ and really does help reduce sweaty back syndrome. It also features the brilliant Crux Reservoir which holds three litres of water. As well as a compartmentalised main storage chamber, the M.U.L.E. Pro 14 has a hip belt with cargo carrying capability (another must) and a removable bike tool organiser wrap thingy. You can also insert optional ‘Impact Protector’ spine protection armour into the pack.

When loaded up and out on the trail, the CamelBak M.U.L.E. Pro 14 isn’t that noticeable — and that’s a good thing! For a very spacious pack, it’s just so damn comfy – no pesky annoyances. The combo of stability and security is adequate without having to wrench the bag around my torso. My overnighter stuff was all packed into the CamelBak M.U.L.E Pro without hassle and if you need to pack a sleeping bag you can do that, thanks to two straps that have little hooks on them; I used these to secure my sleeping bag to the bottom of it. Again, when riding, the bag felt snug and secure — I could feel its weight, but it was well distributed. All contact points for the bag have been carefully considered, with each strap being made up of a cross-hatched mesh, along with a sponge centre for maximum ventilation. The traditional shoulder straps have a runner system for easy adjustment of the chest strap too, which reduces that cutting sensation on the armpits which can be a bloody nuisance with an ill-fitting and heavy backpack.

The M.U.L.E Pro 14 hosts a very spacious 3L bladder suitable for whatever your trail adventure. The reservoir is easily accessible via a full-length zip down one side of the bag — the bladder can be removed and refilled with ease, thanks to its helpful handle design and large opening towards the top. The quick release hose connection reduces faff in feeding it in and is great for cleaning as well. The drinking tube has a magnet on it, so it stays secure while you ride. I think the magnet is great for making a solid connection but, when riding and moving, you need to twist it – which can be a touch difficult.

Overall, the light open mesh absolutely lets the back breath whilst remaining secure. The hip straps and lumbar pad really help distribute the weight nicely. A handy addition is the mesh pocket on either side – big enough for a multi tool or snacks for quick and easy access. The best pocket, though, is the sneaky one on the left-hand side of the pack where the waist strap meets the bag. This little pocket is well protected and will fit your cell phone for snapping memorable moments. It meets all my requirements for storage space and stows enough water. The comfort reigns supreme and it does its job very well. Now, I just have to find some more time for backcountry missions?!

Bosch PowerMore 250 Range Extender: Push the adventure, not the bike

Words Alex Stevens

Images Supplied

If you had a chance to read our last issue, you might recall our review of the Mondraker Dune R with Bosch’s lightest drive unit; the Performance Line SX.

We loved the natural ride feel of this bike and thought that, being a lighter set-up but still with plenty of torque and power, it would be ideal for backcountry and hike-a-bike missions, especially with the addition of a battery range extender.

With Bosch’s PowerMore 250 Range Extenders now available in New Zealand, we’ve had a closer look at this system and can confirm we like what we see. Here’s how it works.

About the size of a drink bottle and weighing in at just 1.5kg, this extra battery provides 250Wh of capacity and can increase range by up to 60 per cent. It’s exactly what you need for a big day out when the plan is to push the adventure — but not end up pushing the eBike home. Knowing that you’ve got extra juice in the tank gives you the freedom to explore further without that niggly range anxiety.

The PowerMore 250 is designed to fit neatly in the water bottle holder on the down tube and connects to the charging port via a cable. The cable doesn’t come as part of the package because the cable length varies depending on the size of the bike frame. It may sound like a hassle remembering to order a separate part but better to have a system that actually fits your eBike rather than making do with a one-size-doesn’t-fit-all workaround.

Cable lengths range from 50mm to 750mm and all you have to do is plug it into the PowerMore 250 and into your charging socket on the frame. The PowerMore cable also comes with two different connector variants: cable routing in the direction of the battery holder and cable routing facing away from the battery holder.

You’re probably asking, is 250Wh enough power? Remember, this is designed to boost your range, rather than act as your main battery. Bosch’s vision for the future is that all batteries in the smart system will become DualBattery- capable, meaning they can be combined for longer and/or more demanding riding.

Saying that, though, you can actually use the PowerMore 250 as a single battery — should you need to. We’re not really here for a quick trip to the dairy, though, so let’s get back to the main purpose: big rides.

If you’re riding an eBike with a mid-range drive unit like the Performance Line SX and adding an extra 250Wh on top of the 400Wh from the Bosch CompactTube 400 (which is presumably what Bosch had planned since these products were all released at the same time), you’ll probably find your legs give up before the bike does. The main advantage here is that you’re carrying less weight.

One thing you will need to check before you get too excited about range extenders, is whether the PowerMore 250 is compatible with your eBike. Even if you’re running a Bosch eBike System it will need to come with Bosch’s Smart System from model year 2024. Check if that’s the case via the Bosch Flow App (settings > My eBike > eBike Pass > Components) or eBike display (Settings > My eBike). If ‘PowerMore’ is an option on the menu that means you can retrofit PowerMore 250. Alternatively, your local Bosch eBike dealer will be able to tell you.

Why can’t PowerMore 250 be retrofitted to all eBikes with a Bosch system? As we all know, Bosch are big on safety features. In this case, it’s about making sure the eBike meets special requirements including, for example, reinforced receiver tubes at the attachment points in the frame.

So, there you have it, an answer to the question we all want answered: how to fit more riding into your life. If you’re on a Bosch-powered eBike, check your Flow App to see if it’s compatible with the PowerMore 250. Spring is here and it’s time to start planning some missions.

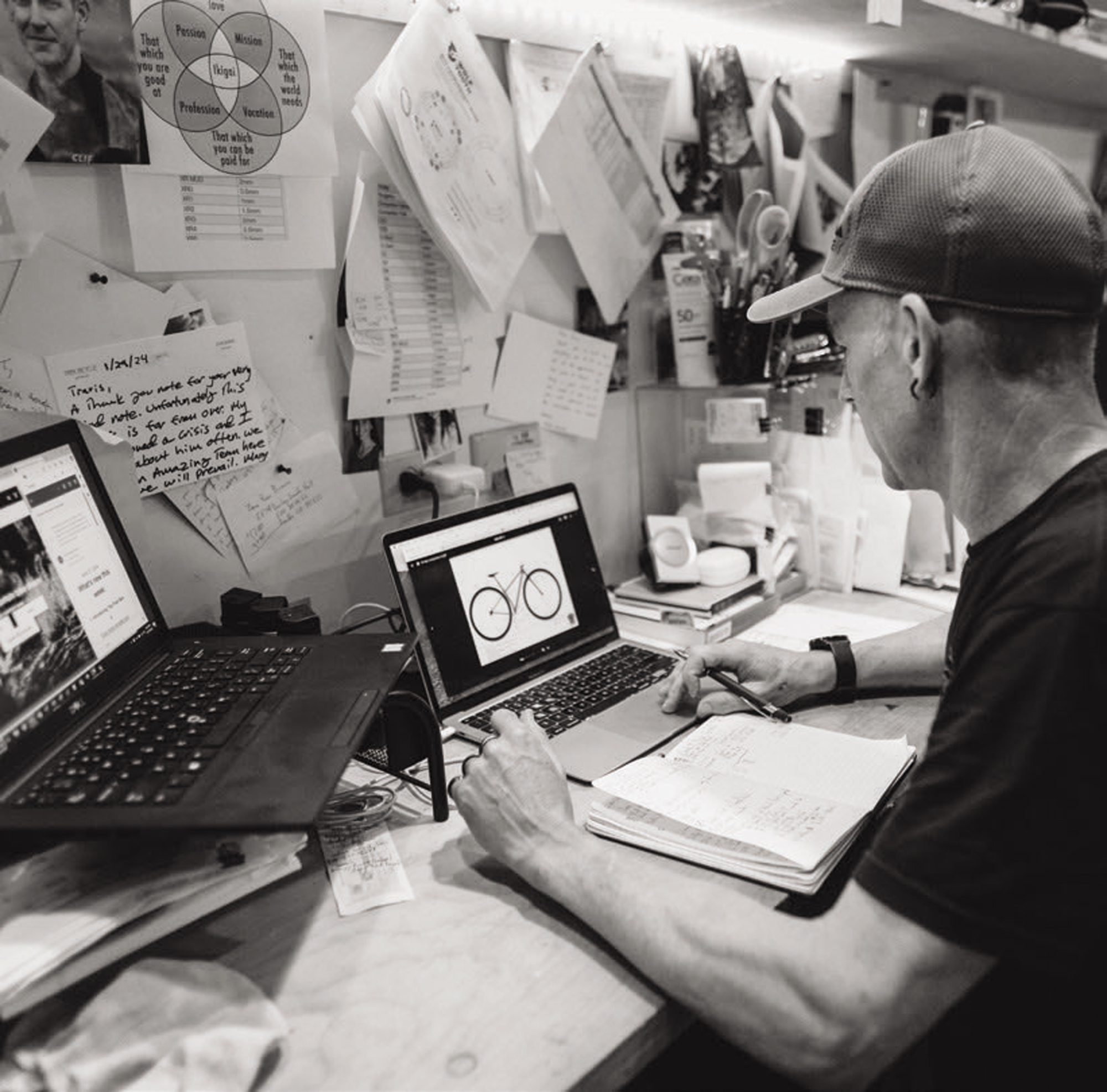

The Life and Times of Travis Brown

Words Liam Friary and Travis Brown

Images Cameron Mackenzie

Skipping our winter on a recent trip to America, I got the opportunity to not only sit down with, but ride and hang out with, the mountain bike icon, Travis Brown. The man – or, more aptly put: legend – doesn’t need much introduction, but for the new kids on the block here’s a brief history.

From the early 90’s, Travis Brown’s professional riding career left an undeniable mark on the sport. He was a regular on the World Cup circuit and claimed multiple national championships in both cross-country and marathon disciplines. At the pinnacle of his racing career, Travis represented the USA in the 2000 Sydney Olympics. After his pro career started to wind up in the mid-2000’s, his attention turned to product development with Trek. These days, he’s the field test manager, running an entire crew of riders who are working on products that we’ll see in the future.

This is the candid conversation I transcribed whilst on a weather hold between a busy riding schedule in Travis’ hometown of Durango, Colorado, in the USA.

Let’s start from the beginning: where did it all begin, for you?

“Well, I grew up in Durango. And went through, you know, student athlete life here — the local junior high school and high school. I did all the ball sports for a while, and Junior High track and cross country (running). Then started focusing on track, like, endurance sports, and did that through high school. I think, like a lot of young people with prestige or hype, whichever term you want, with the Olympic games and professional athletics, that was an aspirational thing — kind of a silly thing — but something that was stuck in my head.”

From an early age?

“Yeah. Running was the first thing where I thought, maybe I’m good enough to dream about that. And that ended early on with some chronic Achilles tendon issues. So, at that point, I changed my focus to cross country skiing. This was in high school. And that was, kind of, a new potential for me. Being in Durango, I always had friends that mountain biked. So, I would train with them in the summer as cross-country skiing training. I then went to the University of Colorado, with a ski scholarship. While I was there, I tried a mountain bike race — because we would train on mountain bikes. In the summer, I was riding as much as the people that were racing mountain bikes. I watched a lot of mountain bike races here before I started racing. It would be live in-person or on TV, as there was pretty good coverage. There were a lot of professionals here in the early days of the sport, like Ned (Overend), who was a local hero. So, that idea that it was something you could actually make a living at, was kind of early seated in my mind.’

When did you do your first mountain bike race?

“I think I did my first race, the Iron Horse Mountain Bike Race, in ‘88. I was going to school in Boulder and ski racing. It was in the year I graduated from high school. The race went great, I was super fit I think at that point; it was [all] beginning, so I think I raced sport or expert — I think after a couple races I got upgraded to expert, in ‘89.

“I actually decided I was going to race quite a bit in expert category. I remember racing the Colorado Point series — which was a big deal at the time — then went to Nationals in Mammoth and won that, and that’s when Worlds were here in Durango (‘90) and I was living in Boulder at the time. I decided I was going to do the qualifying race, so did the pro race here and made it into the elite race for Worlds. Probably just through stupidity of not knowing, not questioning anything, I had a good race and was 10th in that Worlds so then I started asking myself the question like, alright is this the path forward? You know, as a sportsman. If that’s something you want to do – is it going to be skiing or is it mountain biking? I debated internally. They’re very complementary sports but, you know, at some point you’re going to have to specialise [in one] if you want to be competitive at the top level.”

When did you go pro?

‘91 was my first full-season pro, and I raced for Manitou. And that was before the Answer licensing relationship with Manitou. So, that was Doug Bradbury actually building bikes in Colorado Springs and me coming down from Boulder and seeing his shop. The way we got the budget to go racing was through the Japanese importer for the bikes. They were selling them for ten thousand dollars in Japan back then. You know, it was really high prestige. They were like, yeah, a professional racer will help us sell, will finance the race team. Doug called me up and he said, let’s go racing. And after that World’s performance, I had a few options. But, this was one that just resonated with me and I’m really grateful for that because Doug has one of the most natural design engineer sensibilities of anyone I’ve met in the (cycling) industry, and he let me participate in that process and that was kind of the beginning of understanding, you know, the technical aspect of building bikes and geometry. So, he built me a bike and said, ride it and let me know if you want to change anything. And, at that point, I had not studied bike geometry – I didn’t know anything from anything – but I rode it with his stock geometry.

I asked for a bike that was like two inches longer and he was like alright, I’ll build it for you if you want. But, back then, it was like way outside of the box. And again, that was just me not understanding what the standards were. It worked good. That was the bike I raced. There were other people probably realising small tweaks from road geometry to mountain bike geometry were not enough, so the wheelbase started getting pretty long and it was good when you’re really tired at the end of the race and you just needed the bike to go straight with stability.

Then what happened?

“It was the second year – ’92 – as a racer with Manitou; I kind of outgrew that program and so I had a lot of options for the ‘93 season and signed with a team that was a Volkswagen Schwinn, which ended up falling apart in the spring. I told my parents I wasn’t going to graduate school — I was going to race. I had no sponsor to start the race season.”

And was it just budget constraints?

“Well, the person who was putting that program together was not transparent as far as all the deals with co-sponsors had been signed. So, it was going to be a big team, and we were all left holding their dicks in our hands. The season opener at that point was Cactus Cup in Scottsdale, Arizona. I went there as a privateer on a Dean titanium because they were a local Boulder company. I’m like, I’m kind of hosed here, I just need a bike. They were really gracious in helping me out. And I went there and was sick, didn’t race that good. At this point, I’m like, maybe this is a really dumb idea. And I’m sure my parents were thinking that; it’s a dumb idea. It’s a really dumb idea. But I stuck with it and moved back here (Durango).

“I worked in a dental lab and rode — the dental lab made me enough money to get to races. At that point, you know, all races had some prize money. Like if you’re doing well, you could actually make some money and prize money to supplement a budget for a race season. Then Trek decided at that point that it was time for them to have a professional mountain bike team. And so they called Zap Espinoza at Mountain Bike Action. They called him first and said, we’re starting a mountain bike team, and we need riders — who’s left unsigned and who’s available? And he recommended me. Late in the spring (’93), they hired me, and I was the first mountain bike racer they hired. The first professional mountain bike racer the company had. So yeah, that was the beginning of my career at Trek.”

Sheesh, tell me about your pro career from there…

“It was great! I went World Cup racing and got to see the world and got to live my life to its potential as a professional cyclist, but wanted to reach the pinnacle of the Olympics. So, pursuing the U.S. National Championship and trying to get on an Olympic team was a big driving force for me. And, you know, when I switched from skiing to mountain biking it looked like the Olympic part, and being an Olympian, was not going to be part of the picture because mountain biking was not at the Olympics. Then, in ’96, mountain biking got into the Olympics.

“The qualifications for the Atlanta (Olympic) team were held in ’96; it was six races, three in the in the ‘95 season, three in the ‘96 season. I was probably not a favourite to make the only two spots for the team, but I kind of made a level up jump that year and started getting good points in that points chase. By the sixth race, I think Tinker had already qualified. He had an automatic qualification, maybe from a World Cup win. Then, from everyone who was left, I was leading in the points — so that was amongst myself, a teammate, and a few other people that were in the mix — and I was leading going into that sixth race. Then, the day before that sixth race, I’m on really good form, practicing an A and B line, trying to do the A line as fast as possible, squeezing seconds out of the technical feature — and I crashed and broke my collarbone. So that dream was kind of crushed at that point.

“The highlight was that I took the time off and then came back. You kind of revaluate your choices at that point with the let-down, but I decided it was worth continuing to pursue racing and that lifestyle. So, I came back — I think with a new drive — and I won my first big National race in a really close battle with (John) Tomac in Park City, Utah at the end of that ‘96 season. Then in ‘97, ’98 and ‘99 I started winning a lot of races in the US. A similar Olympic qualification process was in place. During the first World Cup, in the spring of 2000, I broke my leg. So that seemed like, all right, this is just happening all over again. Another revaluation of all your choices. I concluded that if I don’t make it, that’s fine; that’s just what’s in the cards. But, if I don’t completely dedicate myself to the recovery, I’ll regret it. So, I was disciplined in my recovery and pushed the boundaries of what the doctors said I should do and came back and was able to hit the last two Canadian World Cups and get more points than the rest of the people — and just squeaked in on that Olympic team.

“So, I got to have the Olympic Games experience that year. In the same year, I’d won the National Championship after many seconds and thirds. I’d kind of checked all those boxes at that point. You know, there was a lot of satisfaction from that and from going through that process, especially being with one company (Trek) long-term and being into the product, into things and asking all the questions like, well, if we change this how would it give me an advantage? I was always asking the engineers about possible opportunities.”

So, that’s how you ended up working for Trek?

“As a racer, I would try stuff that other racers weren’t willing to try because of the risk. And I learned a lot through that process, and I developed a lot of relationships with the engineers and product managers. As my racing career was winding down, I made it clear that I wanted to move into a product development role and focus full-time on that and they (Trek) very graciously gave me the opportunity to do that.”

How did your role with them develop?

“I was focused on the development role as a rider and I was racing a lot still, so it was pretty clear that we needed more than just me out there focusing on testing — so I started building a group of field testers around me to help me figure stuff out. People with different skills, people that could ride different products. Now we have basically a West Coast (USA) group and East Coast (USA) group and the Colorado group — and a group in the Netherlands too. We’ve kind of reproduced what we built here in Colorado in a bunch of other places, globally. We’ll (Trek) continue to do that as we have the resources to do it, because it’s proven to work. You learn a lot and you’re exposed to nuance and opportunity through all those hours of pedalling that you can’t get any other way.

That same application, like training in the field, just married up for me and for my interests and curiosities – it was a complete natural dovetail. It was pretty easy to go from a professional racing lifestyle to a different occupation because I still got to ride a lot, and I still do that now, right?

You still have the passion to ride?

“Yeah, [my enthusiasm] for pedalling has never waned or lost interest, and I have always stayed hyper passionate about the sport. Of course, there are days you don’t want to ride but I have found aspects of mountain bike riding that are really medicinal for me and help make me a better, healthier person. So to continue to be able to do that as part of an occupation is really a blessing. It’s been a great lifestyle for me, and it’s been a great working relationship with a good company — you know, the people at Trek are some of my closest friends and they kind of have a no asshole policy.”

What does the future hold for the sport and yourself?

“Well, its broad. Cycling has all these different nuanced applications, especially the soft surface disciplines that are still evolving at a fast pace. The most recent example is gravel. When I first started mountain bike racing, we all did cyclocross and mountain biking on the same bike. You know, if you look at that bookend to where things are now, that evolution of the sport is pretty profound. The endurance side of things has a whole suite of disciplines. The gravity end of things has a whole suite of disciplines. And so the trajectory of evolution is really still pretty steep. I think that makes the industry really exciting. And it’s still going to continue to grow. Obviously, we have plateaus, and stuff that’s been done and is refined and [made more] sophisticated.”

Do you think that diversification and segmentation will continue within mountain bikes? And then obviously we’re not even touching on eBikes in that sense, right?

“Yeah, that’s an evolution that very few of us would have predicted — and it exploded in a very short period. If you look at that disruption to the bike industry, it’s really like the disruptions that mountain bikes provided the industry in the late 80’s and early 90’s. You know, a huge growth boost that brought lots of new ideas and concepts and technologies and profit opportunities and stability to grow the industry. I think there’s a lot of things about eBikes that are cool. Like the equaliser part — the fact I was able to do a ride with my dad, when he was like 75 years old, you know. And we would have never been able to do that together, if it wasn’t for eBikes. And rides with my daughter and rides with my wife — eBikes allow a different shared experience. [Then there’s] the utility part — where people are getting out of their cars and onto bikes, which is amazing.

It’s about attracting new people to the sport because, honestly, mountain biking is hard — like, really hard. And that was a big hurdle to entry for a lot of people. But eBikes have eliminated that to some degree. It brings new people into the sport. And that’s good for everybody. I understand what an active lifestyle does for quality of life, and I think eBikes are providing that opportunity for people that wouldn’t have seen it otherwise.’

What does the future look like for Travis?

“I ride bikes dictated by the product pipeline, so that’s not total freedom or riding as a pure part of your life… but it does mean that it’s an imperative part of your daily occupation. So, there’s two sides. At some point, I’ll retire, and will be able to ride any bike I want on any trail I want, and I’ll love that — but it’s pretty good right now, too. I can’t complain — I mean, honestly, my whole career (which is kind of avoiding what most people would consider ‘real jobs’) has provided a stability — financial stability — for myself and for my family, which is kind of perfect. It’s kind of a dream to be able to do it that way. So, nothing’s perfect. There are light and dark sides to every part of it, and I will enjoy the freedom of not having that at some point. I’m not counting days until retirement.’

What does cycling mean to you?

“I think what I said before; it’s a really medicinal component of my life in a lot of dimensions. So, it’s an occupation, provides me a livelihood. The physical activity and competition now, I have an appreciation for that component of the human experience that I probably didn’t appreciate when I was racing full-time. Bikes are magical machines which you can ride as far as you like, and it can be accomplished under just human power.”

Lastly, your take on Aotearoa?

“I did a month trip down there after that Single Speed Worlds. There’s a lot of places I’ve travelled to that I’ve enjoyed, but very few places I’ve been to where I thought, ‘I could live here’. For me, New Zealand was like that. I described it like it has everything in Colorado — plus an ocean. It’s your connection to the outdoors and to nature that is important — you get a lot of that outdoor experience. I am scheming up a way to return for a bikepacking trip. New Zealand’s pretty bitchin.”

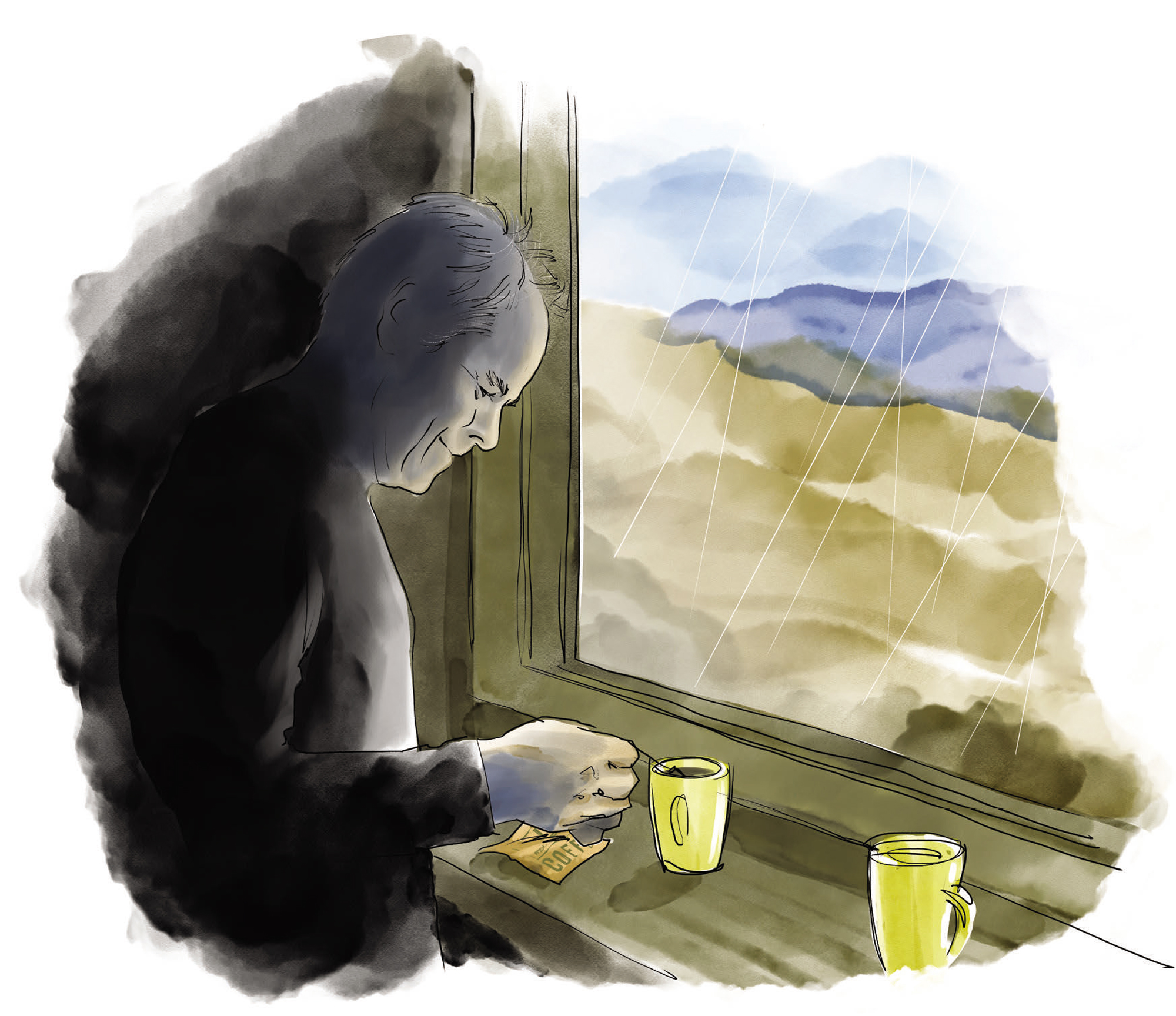

The Maker, Sam Baker

Words Lester Perry

Images Finlay Woods & Sam Baker

How the collision of illness, art, and bikes changed the course of Sam Baker’s life.

From afternoons spent scouring roadside inorganic collections, either for parts or entire bikes, to digging jumps in the back paddock, Sam Baker’s childhood was pretty ordinary for a Kiwi kid in the late 90’s. His earliest years are but a puzzle piece of the guy known as ‘Sam’ to many, ‘Baker’ to others, and ‘Vacation Studio’ to the many brands he now works alongside. Needless to say, the journey of life from those early days in his backyard of Waimauku, to now living in Wanaka, creating graphics and art for many current ‘it’ brands, is a great yarn. Even after knowing Sam for a long while, it’s only now, after working on this feature, that I’ve filled in the blanks and can see how he has ended up doing what he does and why he does it. None of it was by accident, apart from a few pivotal years of illness — but we’ll get to that part of the story.

Raised on a ten-acre block of land in Waimauku, 45 minutes north west of Auckland, Sam’s school and friends were a car drive away, so he and younger brother Zach spent their days racing each other aboard their latest inorganic collection Frankenbikes, unwittingly laying the foundation of their riding skills. With Riverhead forest on their doorstep, the brothers’ lust for playing on their bikes drew them to the area’s notorious trails. “Good in the summer, horrendous in the wet, I kind of just grew up riding there. I was on a 16 inch BMX bike until I was probably 13. That’s all we had. We would just go into the forest on these back-brake only bikes and just bomb huge chutes. And it was pretty wild.”

Aaron Fernandez, now owner of Alta stores in Queenstown, was a key figure in downhill racing in the Auckland area, and a friend of Sam’s father. Seeing how keen he was on riding, he encouraged Sam to broaden his horizons by taking on the Auckland Downhill Series. Now on a larger, better suited bike, a Kona Scrap hardtail, Sam dipped his toe into racing across the Auckland region and so began his journey towards a full-blown bike addiction.

Competition between the brothers helped refine their strengths on the bike. “Especially when we were doing jumps, one of us was learning tricks and stuff, or maybe more style-based; Zach was always way more naturally styley, but I was probably more ballsy, doing bigger stuff. One of us would always be wanting the other person’s (attributes). I could do a bigger jump, but he would do it way nicer, and I was always really angry that he could do it way nicer than me. Then he was angry that I could go bigger or something. The jumps we were building were so sketchy because dad wasn’t building them, it was just me and Zach, a hammer and a couple of nails. And it would be a huge piece of ply with four nails at the top, it would sort of flex like crazy and just springboard you into the air! I look back now (and think) how did mum let it happen? But it was pretty good really, it kind of teaches you to ride anything.”

With access to a digger, the brothers built trails in the yard, eventually building a monstrosity of a pump track. “It was probably like an acre of a pump track. We would just go and add lines that had every possible line option. It was a pretty perfect place to grow up. And I think with it being wet 70% of the time, I look back and I’m kind of thankful for all those wet days because now I love riding in the wet. It’s the best! Whereas generally people kind of hang up the bike for winter.”

With the boys now keen on racing, their next port of call was the infamous Levin Secondary Schools MTB Champs, a three-day competition that drew riders from around the country. They pitted themselves against each other in uphill, downhill, and cross-country, usually using the same bike across the disciplines. This became an annual trip for the Baker family through the high school years. The excitement of racing his peers ramped things up a notch and, after a second place at SS Champs, Sam secured his first sponsor: Bruno at Cyclexpress who helped him to throw his leg over his first proper downhill bike, the iconic Ironhorse Sunday.

By 2007, Sam and Zach had caught the downhill fever. With parents in tow, what was previously their yearly trip to Levin was now a full national race series trip. “We just dove straight into it, really, we went and just did the full series first crack. That was our family holiday. The olds bought a tent and the whole family just camped for like six weeks or whatever it is, down around the whole South Island, just doing the races. I was maybe 16 or 17 when I first did a national series, and I did it every year until 2012, just driving around.”

Sam was selected for the NZ team during his first year in the U19 category in 2009, hoping to represent NZ in Canberra a few months later at the World Champs. Unfortunately, soon after selection, Sam crashed and broke his wrist. With theoretically enough time to recover before Canberra, he set to work making the most of a bad situation. “I was just hedging all my bets on Worlds in Canberra that year. It was a pedally track, and that certainly wasn’t my forte, and I ended up having another huge crash there. My first year under 19 wasn’t what I was hoping it would be; I missed going over to Europe and doing the full trip and everything. I kind of was just sitting at home with a cast training for Canberra, really.”

Putting his lacklustre 2009 season behind him, in 2010 Sam headed for an entire season in Europe, hoping the trip would be a step towards World Cup domination or at least some decent performances. It shaped up to be another year of discontent. “I met Josh Bryson in 2008 (Josh went on to be a high-profile pro) when he came over with his family and did a New Zealand series here. So we’d stayed in contact, and then that was our base initially. We flew into Manchester and stayed with Josh for ten days or so. We used his driveway to build out the van we’d brought, he’d given us a car to go and look at vans and stuff, and we’d go riding with him at the local woods around there, which is pretty sick. Looking back now to see where he’s come from, what he’s done and where he’s gone, is pretty sweet.”

“We were there for maybe three months, we got an apartment in Morzine, based ourselves there, and kind of just picked and chose a few races around and did all the World Cups we could. I remember the first one being Fort William, and that was just so eye-opening, dropping straight into this famous, huge, rough track. Just so stark in comparison to what we have in New Zealand.”

“It was an experience of a lifetime, and I loved it, but I was just at a bit of a crossroads. Like, do I go to Uni? Do I chase it for another year? It took me ages to decide, but in the end, I was like, I’ll go to Uni and get that out of the way, then I can always come back to bikes. It’s kind of crazy; over that time at Uni, the whole mountain bike world sort of changed. There wasn’t enduro racing; there wasn’t any of that stuff back then. Enduro was taking off, and that seemed way more appealing. The travel aspect of Enduro, going into different, more backcountry areas, is a bit more exploratory as opposed to just flat-out downhill race runs. I wanted to do that way more.”

“I wish I could go back and do it again, but I’d teach myself to actually do a job. If I were to talk to my son or something, I’d be like, ‘be something’. Be an engineer or something. I just went and studied marketing; I studied a subject that just evolves and changes so much. I’d always done art and design at school, and I kind of was thinking, oh, you’re in marketing. You’ll be like, the creator of the ads. You’ll be able to make some cool stuff. But marketing just grooms you to be a sales rep, which is not what I wanted to be. In the end, it was great for the experience and developing as a person. The biggest thing Uni did for me was shape me as a person. It narrowed down what I liked and what I didn’t because, coming out of school, I still didn’t know the world. It’s pretty hard to get out of school and choose what you want to do. For me, it was all about bikes at the time. Then I had this other side of me, which was always into making stuff. It was my first time fending for myself, and that kind of aspect of Uni was good, but actually coming out of it with a marketing degree — maybe not so much. I did marketing and economics, majored in both, but haven’t used it since.”

By 2013, and with World Cup MTB dreams behind him and degrees underway, riding was taking a back seat and, unfortunately, so was his health. A trip to the bathroom one day resulted in Sam spotting blood in his stool, the first symptom of his Crohn’s disease and a crucial turning point for everything in Sam’s life.

“At the time, all you think of is, is that cancer? What is that? You’ve got no idea. And it took them quite a while to figure out what it was. I went and saw people; whatever they initially thought it was, it wasn’t. There’s Crohn’s and ulcerative colitis, which are virtually identical symptoms but have vastly different treatments, which is a pain. So they were treating me for ulcerative colitis, which is kind of curable, I guess, whereas Crohn’s is incurable.”

For the next couple of years, Sam underwent treatment, surfing waves of feeling okay, almost normal, then having flare-ups. The disease sapped his energy to the point of being bedridden. “Your body’s fighting this internal battle. It’s like an autoimmune disease, Crohn’s, and so your body is just sending all these white blood cells and pretty much running your body down while trying to fight this imaginary disease. It’s like it’s attacking your digestive tract, basically thinking that the digestive tract is a virus, and it just eats your insides out.”

“I had maybe two years or three years of just kind of, like, blindly thinking that it was getting better, but in my head knowing I wasn’t, and ended up having a huge flare-up. I don’t know what you call it, but it’s basically your body going into shutdown because it’s on its last legs, and you just kind of collapse into nothing. And that wrote me off for a whole year. I just kind of lay in bed and never really got out. I could sort of walk to the letterbox, and that would flog me for three days. I just couldn’t do anything. Yeah, it was pretty wild.”

Unable to work, Sam figured he could expand his horizons. With his previous interest in design and art, he downloaded the Adobe Creative Suite and set to work teaching himself how to use the software. “Every day, I would just sit on YouTube. I’d think of something that I wanted to do, Google it, or watch it on YouTube. Yeah, you can just teach yourself to do design, which was cool, but it also caused a good shift in perspective.”

“The recovery process was crazy. Well, it’s incurable, but you can manage it for the rest of your life. You’re on crazy drugs. It’s all chemotherapy drugs and that sort of thing. The drugs roll you just as much as the actual disease does. I was taking these crazy high dosages, and they wouldn’t operate to take out the part that’s being attacked until you’ve been through every possible drug option. It lasted like a year and a half of trying all these drugs before they’d operate, and I was just getting worse and worse.”

“I was just bleeding out my arse all day, not getting any better. Finally, they said, all right, you can have the operation and cut the affected part out. They ended up having to take out my whole large intestine and give me a colostomy bag. Before I went in for the surgery, my whole body was riddled with scabs because I was so run down. Pimples and all sorts going on, just terrible skin. I woke up from the surgery, and all of that was gone almost instantly. Just straight up. Mum was like, holy hell, I can’t believe this.”

“The recovery process after I got that out was so quick. It had been over a whole year of having no energy, couldn’t do anything. Then, within a month, I was surfing again and out riding bikes. It was just a night and day difference, which is pretty nuts.”

He’s not one to delve too deeply into the dark times of his treatment and recovery, but coming close to death a few times had Sam reevaluating how he looked at most aspects of life, questioning what he wanted to do and how and where he’d like to live. “It was a whole outlook shift, focussing on making every day really good, which I hadn’t done before.”

“You can just get swept up in this whole rat race; get a good job, get a house, follow the normal path, but it’s not necessarily the happiest or most rewarding. So it was kind of a cool shift to make every day feel like a holiday, which is how the name Vacation Studio came about. It’s about just enjoying yourself, I guess.”

Back to feeling himself, and with a new lens on life, Sam moved to Mount Maunganui in 2015, primarily to chase the surf, but having Rotorua’s trails just over the hill was a huge bonus. He began working for George & Willy, a homewares brand started by a couple of his school friends. “I was doing all their woodworking stuff, building all their desks and their wooden stuff, and looking after the warehouse. Just living a really easy, simple life and doing my design stuff in the evening. Then, in 2018, I became intrigued by Wanaka. I’d always kind of skied a little bit, and had done some riding in summer down in Queenstown. I thought it would be good to come down to Wanaka for six months and see what it’s like. I’ve been here for six years. Never left.”

Like everyone who’s moved to Wanaka, Sam has embraced the outdoor lifestyle, and every moment he’s not creating something or working on a project, he’s out in the mountains. Bikes, skis or feet, Sam’s out there getting amongst it. Regardless of what time of year it is, bikes are still at the top of the list, and although his roots lie in the gravity side of cycling, these days, he’s exploring new horizons on the gravel and backcountry tracks surrounding his new home, keen to push his physical and mental limits.

In 2022, as the South Island’s COVID lockdowns were lifting, Sam took on his first multiday bikepacking event: the Sounds 2 Sounds, from Marlborough Sounds to Milford Sound. “The ability to slow things down and simplify life is underestimated in this fast-paced world. There is so much to see, and the humble bike allows you to see it in such a unique manner. This was my first multiday bikepacking adventure and, as I rolled into Milford Sound and marvelled that I got there with my own two very worn legs, I realised I’d be back. I quite like my bike.”

Riding 1450km in six days was one way to break new ground and discover what he was really capable of. Riding the road from Te Anau to Milford and not being passed by a single car is an experience he’ll remember forever — and likely no one will ever be able to repeat!

On December 22nd 2023, Sam continued a yearly tradition of breaking personal boundaries and digging deeper to find his limits and took on an Everesting. He was intrigued by the idea and keen to see if it was as brutal as people make out but, more than that, he just wanted to know if he could do it.

Completing seven laps from the Cardrona Valley floor and climbing to the top of the McDougall chairlift at the top of the ski field brought his total ascent to over the 8,848m threshold. Keen to avoid the monotony of descending down the gravel road, he opted to ride down the Peak to Pub trail with a small bomb down the gravel road to finish each lap.

Sam didn’t have a support team or even a plan for how the day should go; he just loaded some food and his bike into the car, drove out to the hill, and got it done — most of it solo. Twenty-two hours and 30 minutes later, he’d knocked it off. Going deeper than he’d imagined, he’d proved to himself that there was another level of suffering he could reach and discovered that even when in immense discomfort, the body kept giving and kept going.

Sam’s riding style lies between two distinct ends of the spectrum. At one end is his gravity side, where he goes fast, rides new lines, and interprets the trail in his own unique way, 100% focused. And, at the other end of the scale is a more thoughtful, subdued, and relaxed style, almost contemplative. This is where he exists when riding gravel or simply exploring an area by bike.

“I love the gravel side of things. For me, it’s like just riding a bike purely for the sake of riding a bike. Because mountain biking isn’t that. You get a gravel bike out to simply just go for a ride. You’re so much more present, and for me, it’s so meditative. You’re not thinking about what you’re doing. You’re literally just turning the pedals and looking around. It’s a time when I can really process things. It’s a time when I’m doing my thinking, I guess. People always ask me, oh, what do you think about when you go on these 100km rides? And I don’t actually even know. I don’t even know if I am thinking at all.”

“It’s just so meditative that anything and everything that’s coming at you, you’re taking in, and whether it’s subconsciously or not, it comes back out. I’ll reflect back on that when I’m drawing or looking at something down the track. The way that stream ran, or the way those trees were, or how the light hit that rock or something, it’ll come back at some point. If you’re mountain biking, you probably would just fly past it. You wouldn’t know at all.”

“Even if I’m riding at the same place every week, I can still find a new thing to look at and a new angle on something. I just like looking at things from a different perspective, I guess. And that’s what I like about art, photography, design, and all that sort of stuff. I’m just taking my unique view on things and making stuff, I guess. It’s basically just pure enjoyment out of both (riding and art).”

“I’m just really addicted to making things in a bad way! Every possible thing that I need. I think that’s why I’m so into design, it’s the process of taking an idea and making something that someone then puts on a t-shirt or whatever. “Or whether it’s building stuff out of wood or sewing or painting, or anything that requires patience and an idea turning into a form. That’s what intrigues me the most; taking raw materials and then coming up with something new at the end of it is cool.”

A glance at any of Sam’s bikes confirms his addiction to making things. Each of his bikes has unique and subtle twists that make each his own. Some of his fleet has echoes back to his childhood and the inorganic collection Frankenbikes – hunting out obscure framesets from back in the days when he was a kid, cobbling them together with unique, often used, parts. From a twenty-six inch single speed dirt jump bike, to high-performing all-mountain trail bikes and retro-commuters, Sams’s bike rack spans the spectrum of cycling genres and a vast timespan.

Sam’s friendly, relaxed, unstructured, and colourful hand-drawn style catches the eye of many an art director. After getting exposure from well-known and large brands, like Pals drinks, among others, his phone has been running hot with enquiries from people who like his style and want something similar to tie their brand to.

“It’s quite hard to replicate yourself over and over. Like for Pals, for example, they’re a big one I’ve done (work for). So many people message me asking, can I get something that’s similar to Pals? I don’t want just to keep repeating myself; it just becomes boring. Whereas, with Good Lids (a Hemp headwear brand), I get the chance to develop myself and try new techniques and styles that I’ve thought about or want to express. I don’t always want to stay in the same rut and become a repetition guy. My Good Lids work is probably the most rewarding. But every client has their own merits. (Good Lids) just trusts me. He’s just like, right, it’s time for another round of designs. You know what to do. I’ll just send back, like three pages of concepts. Probably 50 drawings, and he’ll just pick and choose. But he just gives me complete creative freedom with it, which is pretty cool.”

“I’m pretty lucky to take it from where it was, just working at home, pumping out my own stuff, to now full-time for the last few years. It’s pretty cool.”

Sam’s a pretty low-key guy. He’s happy to go about his business, and although his work is seen all over the country and abroad, he’s still the same old, down-to-earth, chilled guy. All he wants is to live like he’s on vacation, chill and ride his bike while creating some fun projects, whatever they may be. Sounds like some solid life goals to me!

This abbreviated piece written by Sam summarises his thoughts on his condition and gives a window into his quiet intellect.

I have Crohn’s. I have no large intestine, and my small intestine comes out of my stomach and into a Colostomy bag. I’ve had this since 2015 and will have it for the rest of my life. I accept that. It saved my life, but that doesn’t make it my friend. I get tired of it. Some days are good, and other days I cry. Lots of days I’m embarrassed, if my bag leaks in my wetsuit or into my sleeping bag. It’s not fun, and I hide. And I don’t want to.

It has taught me so much about myself, and for that, I’m thankful. Life is short. Try things, be brave, be uncomfortable, be happy, be kind. It’s hard, and I struggle, and I hide, I’m not brave and not comfortable. But I want to try to be better and show others who battle with themselves that they can try too, they can talk, and they can grow. If you want to talk, ask me.

I’ve been to most places in my head, and I know them all very well. This isn’t a sob story. I don’t want sympathy, but I just want to be braver and more comfortable with who I am. I just want to be Sam — me.

Southern Double Dip

Words & Images Gary Sullivan

We decided to head to the South Island for a holiday because I had just got back from a holiday in the South Island.

I wanted a repeat.

It had been a long five years since we’d last crossed the Strait with our little caravan, and it was an easy sell: Glen is always up for a road trip, and she really loves the West Coast. We booked the first ferry we could get a slot on, hooked up the bach-on-wheels, and hit the road.

That first holiday goes something like this…. Thirteen years ago, a trail was opened that roughly follows a route through the mountains, imagined by gold miners in the 1800s. It’s called the Old Ghost Road, and is a bucket list ride for any keen mountain biker. In fact, it’s such a bucket lister that I rode some of it before it was finished, and could tell back then that it was going to be something special. Nearly everybody I know had managed to organise the time and logistics to get down there, but I hadn’t. Things I thought were more important at the time got in the way. Work stuff, other great rides elsewhere, illness, house building. I just hadn’t got around to it.

Last year, I met up with a friend from Queensland who mentioned he was organising an upcoming junket with some other people. The plan was to do some riding around the top of the South Island, including the Old Ghost Road. I jumped on board.

I met the gang in Wellington the day before we were to make the Cook Strait crossing. John had hired a vintage Toyota Hiace and a trailer for the bikes and bags, which made things simple for me. Get myself to Wellington and ditch my own van at a mate’s place, then relax and ride.

As a bonus, we had time to get a ride in at Makara Peak in Wellington before going south.

I have ridden a bit around Wellington but to my everlasting shame had never made it to Makara, even though it has been in development for something like 25 years. Well, I have now, and it won’t be the last time. It was amazing, and we only dipped a toe in the Makara offering.

The trail builders of Makara hew their routes out of difficult terrain – there is a lot of solid rock to be hacked through. Pedaling out of the main car park, we climbed the sublime Koru trail. It really is a work of art; a climbing trail that is actually fun is a rarity around my way.

Once we reached the summit of the park (which felt like the summit of Wellington), we were treated to massive views, an info station mounted on an outsize bike chain, and even a couple of charging stations for eBikes. I didn’t stick a fork in them to find out, but they looked legit. Just who would cart a charger up there to re-energise for a ride back downhill was not clear, but I guess somebody must.

We took a very entertaining intermediate level run back to where we started, then climbed the thing again via a slightly more taxing route. A few of us took a loop around the high point then jumped on a flow trail back to town. We finished on what some of us reckoned was one of the best bits of trail in our entire trip: it’s called Starfish, and ticks a lot of boxes.

The trip to Nelson took most of the next day, but we still had time to hook up with Mick, a local contact who showed us how to get to Codgers, the trail network closest to town. He led us up another surprisingly pleasant climb to a couple of what Nelson riders consider basic trails. A good way to get oriented, figure out where we were in relation to the riding, and get a taste of the dry and rocky terrain. Back in Rotorua, we have a few rocks in the forest – and we can count them all without having to use our toes. Down here, rocks are everywhere; some are attached firmly to the planet, many are not. In a mellow 18km we still managed an overall up- and-down totaling 726m – that would rank as a big ride back home. Down here, at the ride’s high point, we got a great outlook over town, but also had to crane our necks to look at the peaks behind us, allegedly full of more trails.

There is a mind-boggling selection of riding options down that way, and a couple of days was nowhere near enough to ride even a small fraction of them. We headed out to Cable Bay Adventure Park the following morning. After signing on at a very nicely set up hub, we hooked up with Mick again and crammed 741m of up- and-down into a scant 13km of distance.

We only tackled trails that are tame by local standards, but provided plenty of challenges for me, thank you very much. The first downhill run was called Broken Gnome, and according to my GPS dropped 210m in less than a kilometre. If I wasn’t following a local, I might have chickened out in a few spots but I was already starting to trust the available traction as long as I could stay on the rocks that were firmly anchored. It was steep, and fun. The rest of that ride was a blur, but followed that theme. I have been hearing about a ride near Nelson called the Coppermine Loop for what seems like forever. I was hoping to fit it in while we were stooging around the region. I didn’t expect anybody to suggest doing it late on the same afternoon of the Cable Bay day, but that is what happened.

We headed out at about 4pm. The ride starts with a climb that covers about 20 kilometres at a railroad grade, because that’s what it is. Some 150 years ago, a crew mined Chromite high in the hills behind Nelson, and they used a simple tram line to send the ore down to a depot in town. Horses would pull the empty wagons up to nearly 900m above the town, they would be filled with ore and return using gravity, with a brakeman controlling the pace.

We performed a similar routine, only without horses. And, we used gravity to descend via a much steeper route into a different valley.

The descent into Maitai Valley is half an hour of maximum fun. The trail is dual-use, with signs everywhere reminding you to watch out for walkers. The descent features dozens of beautifully bermed corners which are begging to be railed. There are also lots of rocks. We didn’t see any walkers.

We got back to the motel in the dark, a really big day complete.

Our next destination was Kaiteriteri, a short drive from Nelson and the jumping off point to Abel Tasman National Park. A beautiful spot crawling with tourists and day-trippers, but also hiding a very cool little mountain bike park. Small in area, but with plenty of elevation, it is worth a visit if you are down that way. We started early the next day, to get to the Wairoa Gorge Mountain Bike Park. A visit to this place was another compelling reason to join this junket. It was created, in large part, by a good mate of ours who died way too early. Dodzy was a force of nature, and when he connected, by chance, with a very wealthy guy with an interest in mountain biking, a short-lived phenomenon was born. It’s a whole other story you probably already know, but Wairoa was one of the projects executed by the company formed to develop trails on land the guy owned all over the planet. He moved on from mountain biking, and now Wairoa is owned by New Zealand and leased to the Nelson Mountain Bike Club.

It is probably the most exclusive MTB park in the world. The shuttle-only access to the 70+ kilometres of hand-built trails is usually maxed out at 27 people; the day we visited, there were 18. Two nine-person truckloads of people in a massive slice of forested mountain is pretty much nobody – we felt like we had the place to ourselves. The shuttle is long, and gets riders to about 1200m. The descent is MUCH longer – at the pace I could manage, each run took over half an hour. The trails are graded, and routes have been created using a numerical system to let riders figure out a way down that suits their skill set.

A few of us who rode together, dropped four times – and two hours of riding downhill on fresh trails takes more energy than you might think.

There are three options at Wairoa for accommodation, we were in the largest – a very nice chalet near the base of the gorge. Two other huts higher up look really good too. If you have a gang keen for a weekend away, the Gorge is worth a look.

We tackled the Old Ghost Road as a two-day trip, staying for a night at Ghost Lake hut. There are four huts managed by the Lyell-Mohikinui Back Country Trust which can be booked at the official Old Ghost Road website. There are also two DOC huts, which are first-come, first- served. The LMBC huts are top-notch, and have kitchen facilities with everything you might need except ingredients; there are firebox heaters with wood provided, basic showers, toilets – they are well-insulated and have great locations.

The first day for us was a climb…. 27 kilometres of climbing to Ghost Lake. There is a brief respite halfway up, at Lyell Saddle. We dropped in to the Lyell hut for a snack and a sit-down on the sunny deck, with a huge view over the ranges to the north. A gang of excitable women had chosen Lyell as their first stop on a five- day walk, and they were all either laughing or yelling at each other at once. There were more of them en route, so we were kind of glad to be staying further along the trail.

The highlight of the ride, for me anyway, was the section before Ghost Lake where the trail reaches its highest point at 1344m. Well above the tree line, it sidles along the faces of a ridge, with massive views. We were lucky to have two bluebird days and the outlook from those heights will always be a strong memory of the first day’s ride.

A short drop into the trees brought us to Ghost Lake hut, perched on a ridge and overlooking the distant town of Murchison, where that morning we were buying extra trail food, eating pies and drinking coffee.

I had the foresight to cram a can of beer into my overloaded pack, and I was relieved to find it hadn’t been pierced by anything along the way. I inhaled it on the deck of the hut, feeling extremely fortunate and grateful for everything about the day. It was already cold, and pretty soon it was freezing – literally: when I ventured outside at about 2am for a pee, there was ice on the ground.

John had organised a helicopter drop of food and sleeping bags; the food was freeze-dried and, with the addition of boiling water, turned into something edible. The sleeping bag was absolutely perfect.

Our second day was hard to fault.

The trip from Ghost Lake hut to the finish is 56 kilometres by my count, and descends 1200 metres. There are some seriously cool sections of flowing trail through exceptional forest scenery and I forced myself to stop a few times to look at it. There are also 827 metres of climbing, so it is not an easy day.

The Old Ghost Road was a perfect exclamation point on a quick sampling of the riding in the top of the south.

So perfect, in fact, that I couldn’t wait to do it again. Literally, I could not wait. So I didn’t.

And that is why we headed south a few days after I returned from the first trip.

One of the common themes of the last decade has been a recurring conversation with Graeme, a riding mate. We have talked about riding the Old Ghost Road every summer, and every summer we didn’t get there. Now I had sneaked off and ridden it without him. Another easy sell: we are going down there, we will have a vehicle, let’s get this done.

He signed on, and we set a dateline for the project.

Looking back, it is hard to believe I only got five rides done in a month of wandering around the top of the South, but we were so busy doing bugger-all that that’s all I had time for. Reading books for a start. We try to read books when occupied with normal life, but the luxury of reading one in a single gulp with no stops for any annoying responsibilities is very good. And having a pile of them to get through is even better. We found a reconstituted refrigerator in the main street of Takaka that had become a free book exchange, and we hung around in Golden Bay for a week of bad weather making full use of it.

Loafing along deserted beaches also chopped out extensive periods of time. We are so lucky in this little South Seas paradise, there are so many places that are easy to get to with nobody else in attendance.

Then there are the simple pleasures of doing stuff in a small caravan. Everything takes a bit longer than it does back home. Those are my excuses, but while the rides turned out to be few and far between, they were stellar.

I did a birthday lap of a trail in Whites Bay on our second day in the South Island as a sort of warm up, then spent a few days slacking.

The next outing was another tilt at the Coppermine Loop. The feature of that day, for me, was the feeling that comes with a seemingly endless vista of mountain ranges away to the south of the Coppermine Saddle. There is nothing man-made in view except the trail, and even though Nelson is very close it is hidden and therefore out of mind. It is a ride, but somehow more of an adventure than doing a similar distance and elevation back home.

We visited Kaiteriteri again, had another outing in the great little bike park there, explored Golden Bay between rainstorms, and ended up getting as far south as Hokitika.

The best night of the trip was a simple roadside pull-off, perched on the side of Highway 6, a couple of steps from a wild and windswept stretch of rocks, sand and surf.

My main target for the West Coast leg of the expedition was the Paparoa Track.

We parked up at Punakaiki Campground, an absolute bottler of a place to hang out. Another spectacular beach to explore, Paparoa National Park near at hand, all overhung by massive jungle-strewn cliffs straight out of King Kong.

The campground operates a daily shuttle around to Blackball, where the Paparoa starts. I booked a trip for the following day, and we holed up while the West Coast did what it does fairly often: rain.

The forecast for the next day looked pretty dire, but the day after was not so bad. I switched my booking, and we spent the spare day hiking around in the rain.

When the day arrived, I was up early, packing everything I thought might be needed for a solo ride in remote country. The Paparoa is doable as a single day mission, and that was my plan, but I carted along a pile of food, spares and extra layers just in case it turned into something longer.

The shuttle got me around to the start by about ten. By the time I got underway, it was steadily raining. The rocky trail was drenched. The first ten kilometres is in the forest and, after a short descent, there is a climb to about 1000m that doesn’t let up.

Just before I reached the tree line, I came upon an apparition: two little girls in festive- looking outfits, walking down the trail towards me. They were about six or seven years old by my estimation, and were incredibly cute. One of them politely said, “good luck, you’re nearly there!” I was briefly mystified, but round the next curve was their mother, with an even younger offspring, and carrying an enormous pack. Parenting done correctly.

Soon enough, the trees opened up into the sub-alpine tussock. At about the same time, the clouds lifted, and the first hut came into view.

From there, the trail follows a ridge for what I reckon was the best part of 20 kilometres. It is not easy, constantly rising and falling as it switches from one side of the range to the other; in some places it sketched along the very top of the ridge, only a few metres wide.