The Kahurangi 600

Words Lester Perry

Images Sam Horgan

The Kahurangi 500 is a bikepacking route on the northwestern side of NZ’s South Island, looping around the Kahurangi National Park and surrounding areas. The K5 is generally ridden from Motueka, covering around 500km. In our case, though, to ease logistics, we started and finished the ride in Nelson, pushing the lap to roughly 610km.

Riders take the K6 as everything from an FKT attempt to a week-long holiday mode cruise thanks to multiple public huts along the route. We had a varied crew, made up of has-beens and never-weres. Ex-downhillers-turned-enduro dads, an Iron Man, and even a winner of the prestigious Melbourne to Warrnambool cycle race. We wanted the best of both worlds: a solid effort without the sleep deprivation or hunger bonks of a single push. Allowing four days gave us the perfect balance of pedalling pain and long stationary stints, eating, and generally chilling, mainly talking about the good old days.

With the Kona Hei Hei in for review, I figured it could be the ideal tool for the task, as Kona had been singing its virtues as a bit of a do- it-all bike with a lean toward the XC and trail end of the spectrum. I threw on some XC tyres, strapped on some bags, and got to work.

Day 1. 168km, 2100m, 8:45hrs.

Departing Nelson just after dawn, we headed out through coastal cycle trails to Motueka for a late breakfast. Eggs on board, and some bike setup tweaks done, we climbed the main road up the Takaka Hill, a roughly 15km 800m vertical effort. Plummeting down the Rameka MTB track was only interrupted by a flat for Sam Horgan, and eventually delivered us to the Takaka supermarket for supplies. With no proper resupply for the next 24 hours, we were forced to make an unorganised and lengthy meander through unfamiliar supermarket aisles. Another few k’s up the road and we made a stop at The Mussell Inn, a roadside pub, for a large dinner and some live music. A pint each and the pub stop was done just as the night set in. Into the night and towards the head of the Heaphy track, and our bed for the night at Brown Hut. A sketchy fire dulled the blow of the autumn temperatures as we slipped into a coma for night one.

Day 2. 147km 2336m, 9:14hrs.

After a chilly tin of creamed rice and over an hour of faff, we set off into the Heaphy, only to stop metres in, to remove our lights that we’d just fitted as the sun was up, smashing our intention to be on the trail pre-dawn. The Heaphy is an underrated backcountry trail featuring some great sections of fast-flowing trail. Unweighting the bike to dodge sharp rocks was a challenge thanks to the added weight of loaded bike bags. Today was James Rennie’s turn for an issue. As the clock struck noon, James slashed his tyre, dumping all its air and most of its sealant onto the greasy rocks. Tyre plugs were ineffective, so a makeshift tyre boot was fitted, and James completed his fix with multiple wraps of duct tape around the wheel and tyre. Sure, it was unorthodox, but it held for the remainder of the trip!

The diversity of terrain through the Heaphy is unreal, from trees hung heavy with moss to stunted alpine growth and, finally, we were spat out on a Nikau palm-lined beach on the West Coast. Riding the road for a solid stretch down the coast, our only solace from the headwind was hiding behind Sam, who by some margin was the tallest and strongest of our group. The sun was slowly starting to dip as we came to our next resupply, the Karamea Four Square.

Now fully loaded with food, speculation was rife as to how many climbs—and how far—it was to our next destination and a lay down. Whatever our guesses were, we were all wrong, especially those of us who ended up riding through to Seddonville, overshooting our destination of Mohikinui, where Sam had ridden ahead to ensure the pub was open and order our dinner. With an extra 10 kilometres under our belt after the Seddonville detour, we arrived at the pub in Mohikinui to meet a somewhat concerned Sam, two beers deep, wondering where we were. All was forgotten after a deep sleep in a campground cabin’s saggy bed.

Day 3. 121.62km, 2656m, 9:16hrs.

After the debacle of day two’s extended morning faff, we rose earlier on day three, riding into the rain at 5:45 am. It’s fair to say we were all somewhat dubious about what was to come, not only with the weather but also how tough this day could be, as we would essentially ride the Old Ghost Road in the reverse of how it’s generally ridden.

Climbing from the get-go, we slogged up technical pinches and meandered through dense bush, the last couple of days riding making themself known as the trail began to get steeper as we climbed away from the river.

Skyline Ridge was an absolute highlight of the day. Even on a bike that wasn’t loaded with gear, this would be a tough climb, but add on all the gear, and it was an absolute beast. Steep, rugged switchbacks made picking a line difficult, and traction was a challenge; my legs could only take so much. I was stoked to make it much further than I expected to before detonating, resorting to walking a couple of sections. Arriving at Ghost Lake Hut for lunch, we marvelled at the view and huriedly downed whatever can of energy drink we’d brought with us, washing down yet another muesli bar. A quick top-up of our water supplies and we were climbing once again. Fortunately, it wasn’t long before we were on the main descent, which would take us all the way down to almost sea level. Partway down this descent, we realised the error of our ways. Built to be climbed, this mellow, non-technical descent seemed unending. The only real obstacles to avoid were groups of people slogging their way up towards the hut for the night.

Not far from the bottom, we came across a keen gent who’d been climbing with one of the groups we’d passed earlier. He was descending back to his car at the trailhead, with a completely snapped seat post. Turns out, loading a massive bag with what appeared to be 20kg’s worth of gear, and hanging it from your saddle is a bad idea. Fortunately, it was all coasting back to his vehicle, not a single pedal stroke needed.

Crossing the 21st, and final, bridge of the day, we were done. As the sun dipped behind the hills and we headed into the final stretch of the day, I discovered I’d punctured in the final metres of the trail. A classic pinch flat with air coming out of the tyre bead and further up the sidewall. Mint. A couple of plugs and it was game on for 30k’s of road into Murchison for another FourSquare resupply, a hot roast meal at the pub and a couple of night-caps before passing out in an ice-box of a campground cabin—although no saggy bed this time!

Day 4. 168.45km, 1696m, 8:06hrs

Breakfast was varied. To each their own, as some would say. A tall can of ‘V’ and Cup of Noodles; a Monster and a chocolate milk with a One Square Meal bar; creamed rice, protein milk and muesli bars; our final morning meant all the nutritional rules were out the window. We ate what we had and didn’t complain. On the road pre-dawn once again, this time to the head of Lake Rotoroa and onto the Porika Road climb. To say this climb is horrid is an understatement: 3.2 km long, gaining 454m and an average of 14% with some seriously steep stretches. My average speed was just 4.5kmph! Sam rode the entirety of it with one small dab, and the rest of us slowly dragged our carcasses to the top with a mix of knee- breakingly slow cadence and calf-destroying walking. The beauty of walking parts, though, was that we had a chance to breathe in the cracker views down the lake. Truth be told, once uploaded to Strava, we discovered we actually made good time to the top, compared to many. We’d eked out any remaining energy we had, so after Red Bull, packs of gummy snakes, yet more muesli bars, and some hearty banter, we descended for literally kilometres… right to the door of the Tapawera Four Square for pies, coffee, and lots of food my cardiologist would frown upon.

Following the Great Taste trail towards Nelson, our patience for mellow bike paths had waned, and we cracked on, swapping turns on the front. Needless to say, Sam’s pulls were the longest. Arriving back in Nelson, it was a tough decision between going directly to the pub for a huge meal or doing the responsible thing and packing our bags ready for the next morning’s flight home. Responsibility won, and dinner waited until we’d done our chores. The meal was spent reliving the previous few days, amazed at how much we packed into them and how epic the Heaphy and Old Ghost Road trails are, and all the better when linked together.

My takeaways from the trip were many, but here are a few: Big solo days in the saddle pushing hard are great, but they’re best shared with mates. Going hard and fast is fun, but it’s just as fun to chill in a camp cabin and sip whiskey while whinging about all the climbing you’d just done. It’s all good until it isn’t; being prepared is key to making big days successful and not needing to walk back to somewhere with a broken seat post. The Heaphy is underrated; it’s a fantastic ride, and although the Old Ghost sure gets more limelight, the Heaphy is equally worthy. Always remember earplugs, an eye mask, and a water filter; forgetting these can make or break a trip into the unknown.

Touring the Island of Eternal Spring

Words by Georgia Petrie

Images by Cameron MacKenzie

When you tell people you’re going to do a bike race in Madeira, the first thing they ask is; “where’s that?”. To which I say; “It’s a random island that’s kinda part of Portugal, but it’s its own thing…”. The follow-up question is often: “What’s it like?” – and to that I can’t find enough descriptive words in the dictionary to articulate just what makes it the island paradise that it is. It’s an all-encompassing place; it draws you in from the moment you approach the airport’s precariously positioned runway, which requires a last-minute 180 degree turn to land, and often rounds out the top 10 “world’s most dangerous airports to land at”.

Once you’re on the ground, Madeira’s namesake “The Island of Eternal Spring” starts to make sense – beautiful, century-old streets are dotted with flora and fauna unique to it’s mild climate, where the concept of “winter” doesn’t exist; strikingly green and rugged terraced hills dating back to the 15th century envelop the island’s capital, Funchal, while the island’s dramatic volcanic peaks create postcard-perfect views in every corner.

Oh, and how could I forget the fact that it’s home to some of the best mountain biking trails in the world? Factor that in, and you’ve got the perfect concoction for a bucket list riding destination.

The seed for racing Trans Madeira was planted when I was lucky enough to visit the island in 2024, to take part in a photoshoot. Other than being familiar with the name, because it had hosted the Enduro World Series rounds in 2017 and 2019—and more so, the Deathgrip Movie—I was going in blind. I knew nothing about its landscape, very little about its proximity (or lack thereof) to anything and certainly not that it would take 45 hours and five flights to get there… of course I said yes! We ended up traversing the entire island, a never-ending, sensory overloading, treasure map courtesy of Freeride Madeira—not only are John and his team the premiere shuttle and touring company on the island, but they also build and maintain Madeira’s 200km+ trail network. I also discovered they were the masterminds behind Trans Madeira, a 6-day, 200km Enduro stage race that circumnavigated the island’s extensive trail network across 35 special stages. After being so impressed at the operation Freeride Madeira had built, I knew that any event run by John and the team would be nothing short of well-oiled, packed to the brim with goodness, and that anything you could possibly think of would “just be sorted”. Bucket list item added!

I am fortunate enough to be able to ride from my doorstep, which helped immensely with squeezing in training rides. However, an important caveat to this is the fact that due to that pesky thing called work—a day job coupled with freelance commitments (one of them being designing this magazine, among other things, in my spare time)—the majority of my rides now barely exceeded one hour in duration (two hours maybe, in summer, if you include the post-ride commute to the pub), and whilst I’d completed Enduro World Series events previously, building my fitness to a level that could survive six days of racing was unfamiliar territory. I spent the summer squeezing in 1000m rides as much as possible, coupled with my usual gym work and the odd sanity run and eBike ride for downhill training. I wanted to challenge myself in a totally different way and if I could finish all six days, I’d be happy!

My weapon of choice was the Specialized Stumpjumper 15. This is a comfortable all-day climber in a light-yet-punchy 145mm package, paired with a beefed up 160mm fork for added stability and a mullet setup for a touch of agility. I stocked up on 6x days worth of kit packed into separate packing cubes, ready for each day—I’m a chronic overthinker when it comes to choosing my OOTD (outfit of the day)—as well as 6x days’ worth of snack kits—NZ Natural Confectionary snakes, Bumper Bars, and PURE nutrition gels and electrolyte packs. While I knew there would be feed zones each day, I wanted to be prepared for any hangry emergencies with food I was familiar with.

On a frosty May morning, we departed Christchurch on what was a simple journey…. until our final Lisbon > Funchal leg. Being unable to land in Madeira meant we flew back to Lisbon, only to get straight back on the plane to attempt the journey again—a total of almost six hours to complete a 1h40 journey, ultimately arriving at our accommodation at 2am. No time for jetlag!

Day 1 – 48 km – 1000m up – 2950m down – 7 special stages

Not being much of a tent girlie under usual circumstances, I decided to splash out on comfortable sleeping gear—a Sea2Summit mat of decent thickness, summer weight sleeping bag and adhesive pillow—all of which were worth their weight (excuse the pun) in gold. Waking up to a beautiful sunrise in Machico, the precarious challenge of attempting to put on full riding kit without dragging 10 tonnes of sand into my tent began. I quickly realised that finding a way to keep 6x days’ worth of riding kit contained within the tent, and avoiding a luggage blowout, was going to be paramount in wasting precious mental energy at the beginning and end of each day—especially as each night was spent in a different location.

Day one took us to the East Side of the island, where we’d be starting the day with Stage 1— Boca Do Risco—a previous nominee for EWS trail of the year, that winds its way down beneath luscious canopies of Jurrasic Park-esque bush until shooting riders out precariously close to the cliff’s edge. When I think of Madeira, this trail is exactly what comes to mind; exceptional hand-built, flowing singletrack that’s the perfect blend of fast and technical, all enveloped by endless mountain-meets-ocean panoramas. After shaking the Stage 1 nerves I’d been long anticipating, and despite my immense preference to do basically anything other than carry a bike on my back up a hill, the endless ribbons of coastline and peaks we were treated to en route to Stage 2 was enough to put a smile on the face of even the most dubious hike-a-biker (me). Stage 2—Into the Mystic—took me straight back to the dustbowl of Christchurch, and was another one of Madeira’s gems that I’d been lucky enough to get a taste of previously. Fast and loose with dust-filled corners and off-camber drifting, staying upright was an uphill battle. The liaison to Stage 4 hit, and every doubt I had about being over prepared with my carefully curated selection of snacks quickly dissipated as I munched down a Bumper Trail Bar. The four bags of Natural Confectionary Co. snakes (if you know, you know) paid for itself instantly—especially the positive reception from my UK and Canadian counterparts!

Stage 4—Natal—down into the feed zone at Porto da Cruz, was full on—basically a rock garden for 5 minutes—and my body was starting to feel the fatigue of needing a substantial refuel. These were longer downhill runs than I was used to and, in hindsight, I had insane jet lag that I was subconsciously suppressing (it’s not real unless you say it is, right?!). The PURE nutrition gel I smashed before dropping in was the real MVP, giving me just enough beans to hang on until the most boujee food zone spread I’d ever seen. I rolled up and uttered something that resembled a “thank f*ck for that” and smashed a Red Bull along with a freshly baked filled roll, a pastel de nata and cup of roast potatoes. No, I’d never seen potatoes at a feed zone before (nor pickles for that matter), but yes, I was absolutely here for it. Reaching Stage 7—Hole in One—the view down into Machico was all-time. A little slick at the top, my tired legs and subsequently lazy riding position caused my foot to blow off my pedal, and I was on the ground before I knew it. Weirdly relieved to get a crash out of the way, I fumbled my way down the final rock gardens of the day and straight into a beach swim, finishing the day in 4th overall.

Day 2 – 46 km – 1182m up – 3700m down – 7 special stages

Generous doesn’t quite cut it for the incredible breakfast spread put on by Chefs Robert and Nuno—these guys haven’t missed an edition of the event since 2018, and it’s clear they’ve got mobile catering for 200 people down to a fine art, and that’s no small feat. The beauty of Trans Madeira is that you don’t have to worry about anything—the smallest of details you can think of are all sorted for you, meaning you can focus on your race and truly take in the paradise that surrounds you for the duration of the week. The fact that these guys can move 180 luggage bags from one side of the island to the other, all while managing to feed 200+ humans, are some serious logistical goals—these guys know what they’re doing.

After exchanging some very tired good morning’s and “body’s a bit sore today eh!”, I settled into my routine of porridge with lashings of Nutella and peanut butter paired with a side of scrambled eggs, sprinkled with dribs and drabs of pastel de natas, beautifully baked fresh rolls, cheeses and pastries. Fresh and so well managed—these guys are goals when it comes to logistics. I learnt quickly that I needed to eat as much as possible for breakfast—by the time we’d roll out and hop on the shuttle and reach the start of the day’s stages, a couple of hours would often pass and I was glad to have some sustenance behind me.

We started the day off with Stage 8—the infamous Gamble line—which was a treacherous mix of slick berms, aptly referred to as ‘Madeira Ice’ when wet, and hero dirt. An island favourite, I was a little too cautious and finished the stage wanting more from my riding—though after seeing how many crashes were had, I was pleased to reach the bottom with clean kit! Kept company by my riding buddy Lizzie, who’d made the journey all the way from Pemberton, BC so could share my jetlag woes, I settled into the chunky sealed road climb that was our Stage 9 liaison to Truta’s Trail. A total contrast to Gamble, this stage had it all, including sketchy wet rock gardens—they did warn us this trail does suffer from the impacts of wet weather, and would be changed should there be too much rain. My fatigued arms were holding on for dear life, trying to maintain both speed and grip through chunky rock sections. After catching three riders at various points throughout the stage, and thanking them profusely for precariously allowing me to pass in the most awkward technical sections imaginable, we were relieved—and for some reason oddly confused at just how technical parts of the stage were (perhaps it was the fatigue skewing our perception)—to make it the bottom of the stage.

In contrast, we were treated to absolute loam- filled bliss for stages 10, 11 and 12. As the trails became drier, the day became hotter, and soon we were baking in the sun at the day’s food zone in Porto da Cruz, the infamous Penha d’Águia rock feature perched above us. Stage 14—Santo Antonio—was a personal favourite of mine and suited me well: rocky, fast, technical enough to be challenging and require careful line consideration, but “not too technical to be scary”, and bonus points for no pedally sections. The stage starts in the open, with mind-blowing views of Funchal below.

The ocean seemed like a lifetime away, and hard to believe that ultimately we’d be riding to our new campsite on the shores beneath—I vividly remembered riding this on my last trip to Madeira, and what a privilege it was to have a chance to enjoy it once again. I tried to carry as much speed as possible through the rocky chutes up top before the trail snaked its way into the eucalyptus trees for its second half, Redline, where endless switchbacks meant you could really dial up your pace. I let the bike do the work and focused on enjoying myself. We finished the day off with the aptly known “Madeira massage”—absolutely bombing it down the beautiful, winding streets of Funchal, precariously perched on the hilltop. There’s something particularly magical about riding through town here—whether it was the residents yelling “go girl!” from their driveways, the beautiful ancient buildings or the blooming flora and fauna, it’s a sensory overload. One of the best days on a bike I’ve ever had, and what a treat to finish with a Stage 7 win and a bump up to second place overall.

Day 3 – 40 km – 1174m up – 2600m down – 4 special stages

Day three truly encompassed the diverse beauty Madeira has to offer; a true reflection of the postcard that I so often describe to people when they ask me what the island is like. Seemingly endless breathtaking landscapes paired with some of the best technical flow trails I’ve ever ridden, all in the company of humans that can only recharge your social battery—THIS is Trans Madeira manifested. Starting Stage 15 on the alpine trail, Pico Cedro, the now fatigued arms were given a wake-up call with exposed rocky chutes, with infamous “Madeira Ice” thrown in. The final stint of our Stage 15 liaison was a short hike-a-bike which highlighted the severity of the blisters I’d sustained in Day 1’s beautiful Ridgeline liaison. After battling with blisters in many hike- a-bike’s prior, this was a key concern of mine that, despite all my preventative attempts, had come to fruition—nonetheless, after only two days. Thankfully, it was short and sweet, and we were rewarded with stunning alpine vistas with all of the day’s stages situated above 1000m, enveloped by striking volcanic-rock cliff faces and panoramic vistas of the island below.

While you’d expect the downhill stages to be the day’s highlight, the liaisons were simply breathtaking—that’s what makes this race such an all-encompassing experience— everywhere you look, whether its descending or ascending, is simply breathtaking. This truly is an all-encompassing experience—being able to descend down some of the world’s best trails is just the cherry on top. The liaison into Nun’s Valley is nothing short of spectacular/ breathtaking/once in a lifetime. Situated in a now-extinct volcano, this world-renowned corner of Madeira originates from the 16th century and is a bucket list item for riders and non-riders alike—enveloped by mountains layered with century-old terraces, it’s hard to know where to look first. Although steep in spots and timed at the precarious point in the day, right before the feed zone, the endless views, easy yapping and descent down the infamous “nun’s path” made any fatigue I was feeling somewhat forgettable.

So far, I’d managed to get into a routine when it came to feed zones and hydration, yet for some reason—perhaps led by belief that today would be a “shorter day” (I quickly learnt that such statements should be taken with a grain of salt!)—I opted to omit my usual bread roll, instead fuelling solely on lollies, a Red Bull and some nuts. Our historic tour of Madeira continued as we worked our way through the next liaison which followed the infamous Levadas—irrigation channels built in the 16th century to bring large amounts of water from the west and northwest of the island to the drier southeast—again, a surreal experience for anybody, with or without an appetite for riding bikes. All was going well until I was perched precariously on the edge of a Levadas and lost my footing, tumbling down into the green mass below, only to be stopped by the crevasse between my middle and ring fingers getting caught abruptly on a rock.

I’ve always found the comeraderie between women at bike races to be something special, and let’s just say—when you’re riding for eight hours per day for six days straight, you see people at their most vulnerable, and anything goes when you’re delusional and fatigued. We’d joked that everybody has to have their “tears day”, and today was going to be my day—I was tired, I’d ripped a sock, my finger (and ego) hurt from my tumble, I’d forgotten my headlamp for the [kilometre-long] tunnel, and my decision not to have a bread roll at lunch was biting me (excuse the pun) in the ass. I was over it, and looking down at my Garmin to see that we’d surpassed 1000m of climbing still (after expecting ~850m) with no-end in sight was the straw that broke the camels back. Those moments on the bike where the revolutions are turning, but you’re slogging away on a road to nowhere. Oh, and suppressing three days of jetlag might have had something to do with it, too! After a few tears, some profanities and a few “I’m fine—today is just a day” moments with the other ladies, I was relieved to finally see the top of Ginjas, which constituted Stage 18—and what an absolutely magical stage this was. Only accessible via the Levada tunnel traverse through the mountains, the trail is only opened twice a year for the race—what a privilege. “Best trail in the world” was a common sentiment among riders at the bottom, echoed by myself also! Luscious, loamy sweeping berms that’d make anybody feel like a hero, rock gardens you could float over and roots to pop off for days—all nestled within an incredible green canopy. We were met by an ice-cold Coral, smiling faces and a picturesque descent down into Sao Vincente. Bad day WHO?!

Day 4 – 51 km – 1287m up – 3300m down – 7 special stages

Being awoken by the classic camping sounds of neighbouring tents unzipping, I quickly realised that the footsteps walking past my tent were squelching, which could only mean one thing… wet ground = rain! The camp rumour mill started in the lineup for breakfast—like kids on school camp—“apparently its sunny on the other side of the island” mixed with “I’m going to sh*t my pants if the dirt is wet out west”. After umm’ing and ahh’ing over how to best kit up, a last minute swap from shorts to pants and my Goretex rain jacket stuffed in my frame, we were loaded onto the shuttles in the hope the windscreen wipers would slow down the closer we got to the start of Stage #19.

I feel this is a good opportunity to give a shoutout to the bus drivers of Madeira—it should be noted that Trans Madeira is a mix of pedal- and shuttle-assisted climbing; most days are around ~1200m of spinning pedals, with the remainder being shuttles. While parts of some stages had me whispering a few profanities to myself, the shuttles aren’t for the faint hearted either—a mixture of being precariously perched on the edge of a road that’s a handful of metres in width whilst dodging tourist cars in-between, all whilst winding for endless kilometres—think driving in the tight hilly streets of Wellington…. but on steroids! I looked across to see a fellow competitor hanging on for dear life—any apprehension about the incoming stage be damned, avoiding motion sickness was a challenge in itself!

Dropping into Stage 19—Pargos—we were greeted with a howling wind, drizzle and what felt like a 10+ degree temperature drop with no shelter other than an abandoned cattle shed. Riders set off each day depending on their current overall standing, with two minute intervals in between—you’d be surprised at how many days in a row you manage to be seeded with exactly the same person! You do the math: 140 riders, two minute intervals… if you’re in the front half of the pack, it’s a long wait and, when it’s raining, it’s a cold start with already fatigued muscles.

Fortunately, for the last three days of racing I was seeded with an absolutely epic UK bunch who provided excellent chat, laughs and some reassurance when I felt genuinely concerned I was about to get blown off my bike into a rock garden at the top of a 1500m hill. Many competitors I spoke to had done the event multiple times, with this group having completed three editions, whilst others had done five or six. After completing one edition, I’ll be buying lotto tickets for the rest of my life to have every chance of coming back for more—I’d have to turn off all social media for a month to have any chance of overcoming FOMO should I not be fortunate enough to be part of the chaos again!

Some say, ‘the West Side is the best side’, and I can’t argue with that! Nestled on the faces of Ponta do Pargo and Prazeres, Stages 19-25 were among the best trails I’ve ever ridden—anywhere. Words can’t capture the pure elation of reaching the bottom of each stage, so I’ll borrow the most common sentiment of the day: *that was f**king sick*. I’d been fortunate enough to experience this side of the island previously, but it quickly became clear that I’d only had a small sample, when in reality there was a full smorgasbord of luscious trails. Natural rock gardens kept me on my toes amidst red-dirt singletrack, lined with luscious Madeira greenery that created a strikingly beautiful contrast, so much so that it was easy to forget you were even racing.

Liaisons were hard that day—grassy 4×4 tracks made for slow going on the climbs, and my blisters were such that I found it more comfortable to pedal at a ridiculously slow RPM vs. pushing my bike like the majority of those around me. The sun gods blessed us with their presence in the afternoon, and we were treated to high-speed, loamy goodness with some dustbowls thrown in—four seasons in one day! I found myself in a comfortable spinning rhythm on the final liaison, and sent a quick Snapchat to my wonderful cheerleading friends and family at home, wondering how I was going—I remember none of what I said other than; “it’s really f**cking hard but this is the best thing ever”.

Now, I’m never one to decline a mojito and, upon reaching the sandy shores of our camp in Calheta, I couldn’t say yes quick enough to the offer of a sit down and a cold bevy! After being politely told “GP, you look like you need a sit down”, I handed in my timing chip and parked up on a sun lounger overlooking the shoreline. I wasn’t surprised to see I’d finished the day in 4th—I was riding tidily, safely, but definitely had more raw speed in the tank, especially with the knowledge of a Day 2 stage win in my mind. While I wanted to slot back into 3rd overall, the elation of simply reaching the pointy end of the race was an achievement in itself, and with two days of racing to go, anything can happen—that’s the beauty of multi-day racing!

Day 5 – 38 km – 930m up – 2900m down – 6 special stages

Day 5 was a much shorter day, again dominating the west side of the island, with just five stages and no feed zone as we were scheduled to board the ferry to Porto Santo at 7pm. Once loaded onto the party bus again—and when you’re sitting with the Irish crew on the floor of an overcrowded bus, there really is no truer descriptor—the rolling circus made its way to Galhano, where we witnessed the most impressive clifftop three point turn we’d ever seen upon drop-off. Unfortunately, we left the sun down in Calheta, along with the Aperol Spritz and mojitos, and were once again faced with gale force winds, heavy drizzle and hydration mix that my tastebuds could’ve done without after five days of consumption. Stages 26-28 were exposed along the ridge-tops and my fatigued brain was working overtime to keep both wheels on the ground and my eyes on the trail ahead, especially as this was narrower singletrack than the days prior.

By this point in the race, the arm and hand pump was unreal—I had anticipated this being the case as I’m certainly not used to riding a bike for six days straight (I wish!), let alone descending thousands of metres, but I had underestimated just how much it would impact the rest of my riding form. I was compensating for my tired arms but stiffening up the rest of body, which meant I was getting pinballed around and pushed off-line easily when hitting big roots, rocks and holes. I’m a flat pedal rider, and I was getting sloppy with my weight distribution—I was blowing my feet off the pedals left, right and centre. I know when I’m riding slow and when I’m riding fast, and at the end of each stage I felt that I had so much more speed in me, but I also knew that I was at the limits of my fatigued body’s capacity to ride safely, and I was riding with a consistency that had me in 3rd overall, which well exceeded my personal goal of simply finishing the event.

I was being well and truly tested, and my mentality was playing a crucial role in ensuring my mindset was in check. I spent much of the stages talking to myself and focusing on remaining composed, especially through chunky sections, as I knew that any drastic line mishaps could result in a mid-stage lie down. Yes, I was sore, cold, tired and my blisters were hurting; yes, I was a little frustrated at my riding; and yes, I knew I wasn’t riding my best. On the flip side, each stage finish brought us closer to the end of the race. I was surrounded by great people, in a beautiful island paradise, living a bucket-list dream I’d worked so hard to prepare for in the months leading up to that moment.

Any misgivings I’d have about how I’d ridden a stage were gone in the 30 seconds it took for the crew I was riding with to reach the finish line, drowned in a sea of collective excitement and relief that we’d survived! Yes, the physical component of a multi-day event is crucial, but keeping yourself in check mentally is equally important. The highlight of the day was Stage 29—Mamma Mia—where we broke through the cloud, and dirt sliding was replaced with dirt surfing upon being treated to delightful loamy goodness.

Day 6 – 35 km – 1350m up – 1350m down – 4 special stages

You’d think that after five nights of tent life, I’d be looking forward to sleeping in an actual bed at our hotel on the island of Porto Santo. Whilst this was true, there simply aren’t enough positive phrases in the dictionary to describe how excited I was at the concept of emptying my entire bag onto the floor, as well as having a bathroom to myself, and all the space in the world to battle with getting my knee pads on in the morning. I can’t even begin to describe the relief I felt walking out the hotel room door on day six—my mindset was focused on finishing, and all I was visualising was reaching the bottom of Stage 35.

The blisters on each of my heels were now the size of Ritz crackers, and we were in for a 1350m climb day, most of which would be hike-a-bike. I was lucky enough to ride these stages in a girl’s train with Becci Skelton and Amy Watts, with Becci aptly describing the overarching sensation associated with any hike-a-bike as being “irrational irritation”—a sentiment that couldn’t be more accurate, and characterised my feelings toward the entire day. I’m not sure if it was to our benefit or detriment that we could see the entire hike-a-bike distance from the bottom to the start of Stage 32—we were midway through the pack on our way up, watching the riders wind their way up the hill face, little ants in the distance. I toggled between my bike on back and pushing it up the hill and, funnily enough, neither provided any degree of comfort.

Across all four stages, we were treated to fresh, never-raced trails enveloped by all-consuming rugged coastal vistas, in some cases barren in a way likened to no-man’s land, or Mars (whichever way you’re inclined). After girl party training our way down stages 33 and 34, the relief of reaching the start of Stage 35 after six days of riding was inexplicably good. Honestly—the rest of the day was a blur. I’m not sure if I erased the hike-a- bikes that followed from my mind or if it was the post-race beers on the beach after completely depleting myself of energy and fluids, topped off with copious poncha’s (a Madeiran speciality) that followed, but I was satisfyingly knackered. I ended up finishing 3rd overall in the women’s category— as if completing a bucket list item wasn’t enough of a treat! For the next three days I felt hungover—not from the ponchas, but from finally standing still after six days of nonstop movement.

All in all, this was an absolutely incredible journey from race sign up to the final post stage high- five’s in Porto Santo. If this isn’t on your riding bucket list, make some room and add it now.

Expedition Pakistan: Riding Gilgit - Baltistan

Words by Mike Dawson

Images by Adam Kadervak

The idea for this mission kicked off in classic style; a post-ride beer session in Rotorua, talking big dreams and wild ideas. Ideas like:

What if we rode Pakistan? The thought of biking a region bordering the Himalayas, Hindu Kush, and Karakorams, with its mind-blowing scenery and raw, undiscovered trails, was too good to ignore. Fast-forward months of meticulous planning, permit wrangling, and local connections, and we were on a plane bound for Skardu, ready to ride where few had ridden before.

Pakistan is rarely the first place that comes to mind when you think of world-class MTB destinations. But that’s exactly what made it so intriguing. This wasn’t a place packed with bike parks and guidebooks—it was terra incognita, a place where every trail was a new discovery and every ride an exploration. This was adventure riding in its purest form, with no safety net.

Our dream team was made up of a killer crew of riders from Rotorua, New Zealand, bringing the perfect mix of skill, stoke, and a positive attitude. Leading the charge was Jamie Garrod, mastermind behind New Zealand Mountain Biking, whose guiding expertise was invaluable.

Matt Miller, the tech wizard and founder of Brake Ace, pushed gear performance to the edge, while Jeff Carter, a world-class trail builder, had an unmatched eye for perfect lines. Adam Kadervak, the cinematic genius, captured every insane moment through his lens, ensuring the adventure was documented in all its glory. Rosie Clarke, a Rotorua ripper, was ready for the ultimate challenge, bringing fearless energy to the group. Rounding out the squad was Mike Dawson, a whitewater kayaker turned MTB explorer, diving headfirst into the unknown.

Rolling into Skardu, the gateway to the world’s highest peaks, was the moment it all got real. The town buzzed with life and rich culture, dwarfed by 7,000m+ peaks standing like ancient giants. Local hospitality was next-level—warm welcomes, endless chai, and curious smiles on weather-hardened faces set the tone.

We loaded a couple of old Toyota Hiluxes, using a little local ingenuity (plus some sleeping pads and carpet), and had the bikes strapped in. The road to our first trail was an adventure all on its own— leaving Skardu, we ascended onto the Deosai Plateau in a chaotic mix of dust, rocks, and sheer drop-offs that kept us white-knuckled the whole way. Our local crew, Taju and Hamish, navigated the hairpin bends with the casual confidence of people who’d done this a thousand times, dodging cows, boulders, and the occasional landslide as we climbed higher into the mountains.

Our first taste of Pakistan was an ordeal. From the Deosai Plateau, we had spotted a faint shepherd’s trail climbing over a high pass, dropping into the Sok Valley and tracing the river from its mountain source thousands of metres down into the Indus Valley. It looked like an absolute dream—an untouched descent of epic proportions.

But reality hit us hard.

Almost immediately, the altitude kicked in like a hammer. We crawled up the climb, battling brutal headaches, stomach discomfort and waves of nausea. It was survival mode—legs like lead, lungs burning, bodies completely unacclimatized to the thin air. The higher we climbed, the worse it got. Finally, we crested the pass, convinced we were about to drop into endless hero dirt. Instead, what lay ahead was a nightmare of boulders, relentless bike carrying, and scattered sections of rideable trail barely enough to keep our spirits alive.

Darkness fell and suddenly we were lost; cold and dangerously unprepared. No proper food, little warmth; our bodies running on empty. Desperation kicked in as we stumbled upon a derelict rock shelter, where we built a small fire and huddled for the night, teeth chattering against the harsh alpine air.

Morning brought a new mission: survival riding down to Sok Valley. Sore, exhausted, but driven by sheer necessity, we began our descent. With every metre we dropped, the trail transformed—what started as a mess of scree and loose rock slowly turned into bedded-in singletrack, winding through exposed ridgelines and sheer drops. It was technical, sketchy and terrifying—but also completely exhilarating.

Later that afternoon, we finally rolled into the first village; drained but stoked beyond belief. It had been one hell of an introduction to Pakistan—a brutal, beautiful lesson in what adventure really means. This was definitely Type 2 fun.

We continued on our mission, driving through the Indus Gorge to the Gilgit Valley for our next stop: Rakaposhi (7,788m)—climbing to the base camp of one of the most stunning peaks on Earth. After a rest day exploring the dusty town of Gilgit, we pushed deep into Hunza Valley, arriving in Minapin. From here, we shouldered our bikes and began climbing. The ascent was brutal—endless switchbacks, scorching sun, lungs burning. But our altitude adaptation was improving, and our excitement fueled us forward. Alpine meadows gave way to glacier-fed rivers, scree slopes, and ridgelines begging to be ridden.

After a night at high altitude, we woke to sun-drenched peaks and began perhaps the best descent on the planet. Over 1,500m of drop, over 10km of wild singletrack. The mix of fast, flowy sections, steep rock gardens, and tight technical moves kept every rider on their toes. This was raw, natural riding—nothing built, nothing groomed— just pure stoke at the discovery of an epic trail.

After refuelling on slow-cooked lamb curry and a few Cokes, we set off for our final mission—Fairy Meadows; the legendary alpine pasture beneath Nanga Parbat (8,126m).

The journey up was insane—2,000m of elevation gain, bikes strapped to the back of tiny Jeeps, inching up a sheer cliffside road. By nightfall, we were hiking in complete darkness, and the altitude was hitting us hard.

The payoff? Waking up to an unreal sunrise over Nanga Parbat. Then—time to ride. The descent was absolute madness—natural flow sections, chunky rock gardens and exposed ridges. Donkeys popped out of corners, the views were unreal. By the time we hit the valley floor, high fives were flying and stoke levels were through the roof.

Pakistan delivered the adventure of a lifetime. Gilgit-Baltistan is an untamed paradise for mountain biking—huge elevation, jawdropping scenery and raw, technical terrain. But this trip was about more than just trails—it was about the people. The hospitality of northern Pakistan was unmatched—locals welcomed us like family, sharing their food, stories, and endless cups of chai.

As we packed up and boarded our flight out of Skardu, still covered in trail dust, we knew this had been no ordinary adventure. It was a fullblown expedition into the unknown—one that redefined what’s possible on a mountain bike.

The trails are untouched, the mountains are calling, and the next great ride is waiting.

Southern Legends: 100 years in one trip

Words & Images Jamie Nicoll

The St James area did not pull my strings until I bumped into Johno while on a bike launch assignment, checking out the new Hanmer Springs trails. My eyes were opened to yet another hidden world of magical riding and scenery to be treasured!

Johno is a pioneer of new trails and a visionary of our sport – in other words, he’s exactly the sort of person I try to find so I can tell their story. Johno works alongside Mark Ingles… yes, the legend himself. After losing his legs to frostbite in an alpine survival situation, Mark has gone on to inspire many generations through motivational talks and projects like this one; the development of the St James. This was to turn out to be a week of Kiwi legends! Johno and Mark are working together to breathe epic style into Hamner and the surrounding remote St James ranges. These ranges are steeped in history and the romance of a rugged life of working the land on horseback—and this is not just history but a present-day reality: I met a horseman out earning a crust through trapping and track maintenance.

This is a place where you can ride for miles and stay in huts; it’s basically an Old Ghost Road or Paparoa trail, except that it has always been there and therefore hasn’t received the marketing attention. All you need to do is look at a map, follow the dotted lines between huts and you are done; you have created your own hut-to-hut adventure on good trails and singletrack with epic views. This area sports a lot of good weather days too, which is worth noting in case you were planning to ride into the mist and rain elsewhere.

Now, I live in Motueka, and I like going places via routes less trodden, so I turned the key on the tried and tested, global-expedition-equipped Land Cruiser with a bike strapped to the back, and headed for the rough roads. From Blenheim, one can access a gravel road heading south 120 km through the Molesworth Station, NZ’s largest station, and the road to Hanmer Springs. The Molesworth road is gravel and remote but can be driven in any sensible car, and allows you to drop into the back of the Hanmer Springs township.

After two days of touring, we pulled the trucks up at Johno’s house for an evening of poring over maps. The next morning the plan unfolded, with Mark Ingles shuttling us out to the start of Fowlers Pass on the Rainbow Road while my trail building mate, Sam, and his brother, drove the two Land Cruisers into a side valley to set up a welcome camp at Scotties Flat hut.

Fowlers Pass has a lot going for it. It sits at 1296m altitude with a smooth singletrack climb and loads of promising and stunning terrain. This was the start of chasing Johno on his eBike for the day. With a good portion of the climb done, we rounded a corner and there was some real-life Kiwi-as-you-get, grey-bearded, Swandri-wearing, horse-packing dude cruising along beside his mount. His name was Sean. His horse has no name but carried the most basic of set ups, using sacks as saddlebags—I thought I’d hit my head and gone back in time! Sean spends 11 months of the year in the backcountry, trapping possums for fur and repairing trails so horses – and subsequently, bikes – can pass through unhindered. Sean is actively involved with a group that focuses on establishing and re-opening historic horse trails throughout the South Island. Man, did this guy blow my mind… legend!

Descending off the pass, tight schist-y singletrack turned and a smooth, narrow thread of trails snaked down the open landscape. This had me back in France, and the trails of the infamous Trans Provence race.

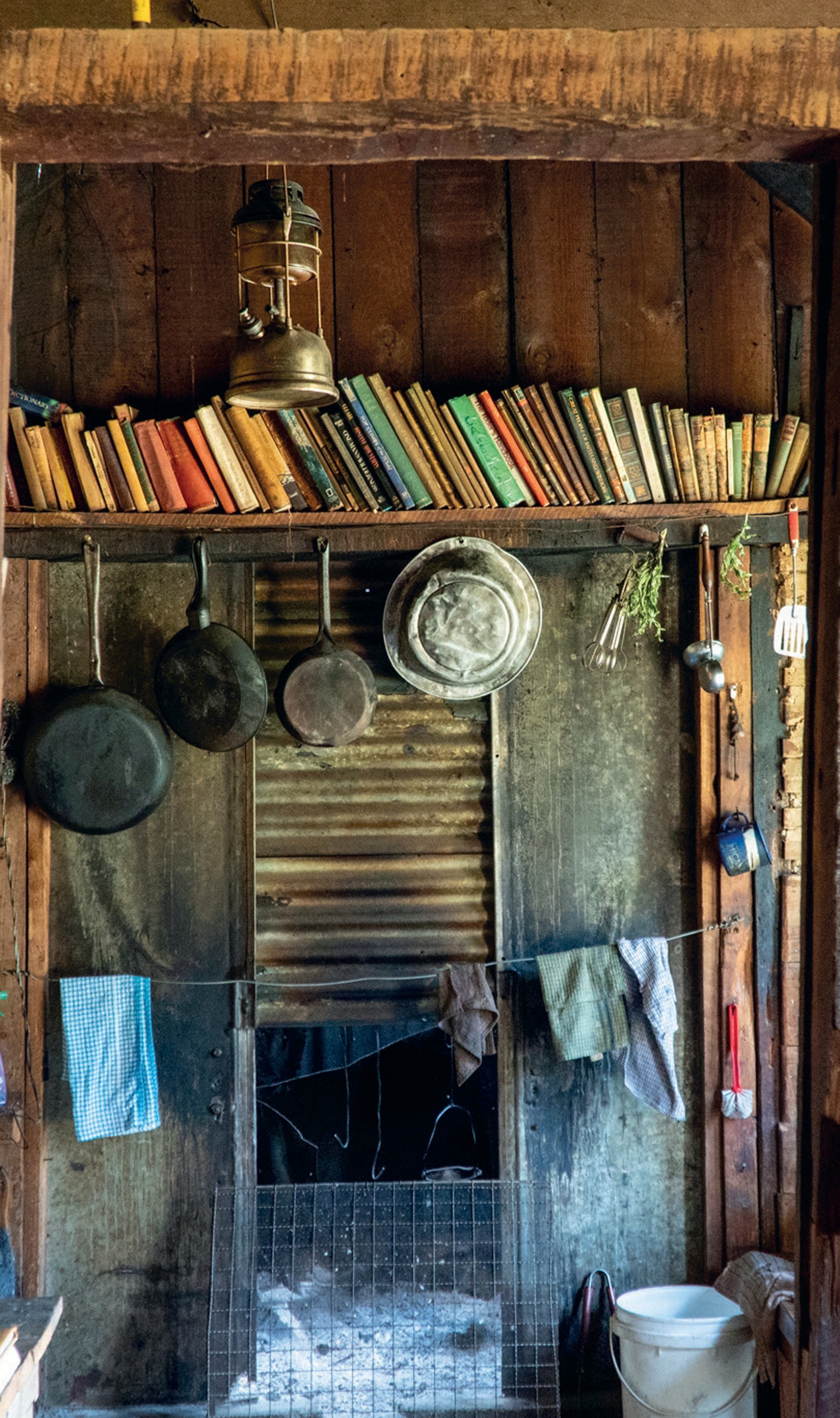

From a plateau meadowland, we peered down at Lake Guyon. Johno pointed out and explained more about the future trail development and links that will expand an already stellar array of backcountry and multi-day options. Think of it as a choose-your-own-adventure location. From the plateau, it was not far to the historic Stanley Vale Hut, dating back to the 1860s with remnants of wall paper and Mother Mary still hanging on the wall. I’d been told a story about some cyclists who had been snowed in at the hut, with Sean keeping them well entertained with stories over the bleak days!

The Stanley River, running south from this mountain grassland, boasts yet more singletrack. We generally maintained a nicely efficient pace, until we eventually climbed up out of the Stanley to ‘The Race Course’, something of a wide clay flat area. Again, you are privy to some of the most impressive views out west, up the Jones River and south down the Waiau.

Some 35km and six hours later we descended to Scotties Hut, down a newly cleared singletrack to a sweet welcome party of Sam and his adventurous kids. These are impressive kids—back home in Motueka the two of them spend days out playing in the forest while Sam is digging new MTB trails for a crust.

That evening, we headed to a remote “wild” hot pool not far from Scotties Hut. Wedged into a small side valley and beautifully located on the stream edge, the starry night above created a fine finish to a big day in the saddle.

Johno had only used 45% of his battery running on Eco for the day, but my legs were definitely spent. This was day four; bikes strapped to the Land Cruiser and headed out, we turned north towards Lake Tennyson and, more precisely, the rough road up to Mailing Pass. Standing at the 1308m pass we looked once more down to the beautiful grassland of the Waiau River flats. Johno pointed out the large pockets of beech forest nestled into the western folds and enthusiastically shared his trail vision for this descent, something worthy of a trip in its own right, once it is built.

With special permission from DOC, we were able to make a quick trip to look at Lake Guyon from the opposite angle. Standing at the Lake Guyon hut, we looked over this alpine lake up to the plateau edge I had looked down from only the day before. This gave me a good picture and understanding for the singletrack trail vision that would link these two tracks with not just old 4WD trails but outstanding singletrack terrain, making even more options for MTB backcountry adventures here!

Tired but stoked, we took shelter in the Island Gully hut in the middle of the scree-clad mountains of the Rainbow Road. Another night in the hills rounded out an epic adventure, rather than the all too familiar story of getting tired and over-focused on getting out. A fresh and happy bunch rolled back into the Motueka Valley with new and exciting trails under our belts and an eagerness to return for more!

The Longest, Longest Day

Words Tom Bradshaw

Images Peter Wojnar

The idea was simple: fly to the Yukon, arriving at 11:59pm on Friday night. Greeted by the midnight sun of the summer solstice, we’d leave the bike bags somewhere and start riding. We’d ride the stunning Whitehorse trails until the 5pm flight on Sunday night, returning to Vancouver in time for work on Monday. No accommodation, no vehicles—just a big ride with plenty of stops and the occasional nap under the midnight sun.

It was ambitious to say the least.

Landing at Whitehorse airport ahead of schedule at 11:30pm on the Friday, we feverishly built up our bikes outside the terminal, in a twilight haze of disbelief and—to be honest—tiredness.

The Yukon is known for its remoteness; the gold rush, the Arctic Circle, and beautiful, expansive terrain.

It’s five times the size of New Zealand and, more than once, we would find ourselves “Yukon’d.” If you were to look up Yukon’d in the dictionary, it would be a verb describing the moment of realisation that, three hours into a climb towards a mountain top, it appears no closer than when you started.

The Yukon is less well known for its mountain biking, however, it is outstanding. The soil is a blend of water-sapping loam and near-sandy alpine dirt. The tree line stops at 900m of elevation, providing “easy” access to the alpine. The vastness cannot be underestimated.

Immediately, our plan was derailed. Unable to simply leave our bags in the bush by the airport as we had planned, we dragged them with us to the local bike shop. I-cycle, arguably the best named bike shop in the world, fortunately has a perfect covered patio where we left the bags. We began pedalling, into the darkness—and the rain.

As it transpires, even during the actual summer solstice the sun technically sets for about one hour. At this point it was 1:30am on the summer solstice and, because of the rain, clouds and technical twilight, our mood matched the unexpected darkness of the forest around us. There was no traffic and as we left the city limits, we realised how dark, wet and dumb this idea actually was.

Three hours later, at 4:30am, we finally broke the tree line. The 1000m climb had taken it’s time, as we paced ourselves and got lost a handful of times up the ever-expanding forestry road network. The visions I’d had of a four-hour-long twilight, painting the alpine and expansive Yukon landscape shades of a Picasso art piece, couldn’t have been more than a fever dream at this point. It was lightish, however, a grey misty cloud had settled, enveloping not only the sunrise but the view of Whitehorse entirely. At least we only had another 20 hours to go, a chance for the weather to clear.

As soon as we started heading downhill, the first bonk of the day disappeared. The low angle 800-metre descent was delicious, albeit spicy with the wet slick roots ready to catch a front wheel. The dirt was perfect, though, and held the moisture well.

The final 150 vertical metres was such a treat that we pushed back up and did it again. By the time we got to the bottom, it was 7:30am, and thoughts of hot, fresh coffee were pulling myself and Jacob to town. Fortunately Peter, who was also lugging around a camera, wisely told us we were being cowards and our short-sighted goal of hot coffee would add another 25km of road to our ride.

The mountains and their bike trails completely encircle Whitehorse. We had headed out to the west, and our next trail lay northwest of town. If Jacob and I were left to listen to our caffeine addiction, we would drop 400m elevation and have to ride back up the same road; it was a dumb idea inside a dumb idea. Instead, we listened to our bodies, and all promptly fell asleep. It’s amazing what 24 hours awake can do. We found a shelter, and passed out on the gravel like it was a California King. Some 20 minutes later, refreshed, we started climbing again—this time aiming for our second 1000m climb for the day: Whitehorse’s downhill track. The climb flew by; the proper daylight, improving weather and incoming fresh singletrack had us moving.

Haeckel Hill DH did not disappoint. Dropping in at about 10am we were treated to a handful of steep chutes with beautifully placed catch berms. The trail then went to that outstanding Rotorua- esque low angle, off the brakes gradient. We were riding like we hadn’t been moving for nearly 12 hours with 2000m of climbing under our belt.

After the 700m descent of beauty we had earnt a coffee. And a beer. This turned out to be a near-fatal mistake. Rolling back into downtown Whitehorse sometime after noon, we had been moving for about 12 hours and were all completely soaked. The bottoms of our feet resembled the contours on a topo map. They did not look pretty, nor did we. We were accepted to the local pub and found a table amongst the locals enjoying a rainy Saturday lunch. Fortunately, the people of Whitehorse could not have been more welcoming. They all seemed unperturbed by our soaking wet carcasses, and we celebrated the halfway mark by toasting to being inside and warm. The consequences of that lunch beer were almost immediate. It was all we could do not fall asleep in the warm, dry pub. Knowing we couldn’t afford to totally piss off the locals, we settled up and promptly fell asleep on the park bench across the road.

This was not the alpine wildflower bed sunshine nap I had envisioned when scheming this mission. But at this point, none of us could care less. Awaking to rain falling on us again, and seeing that it was 2:30pm, we decided we should really get going to climb up Grey Mountain, a 1400m mountain to the east of town.

Over the next three hours, we learned the hard way about the term “Yukon’d”. By 5:30pm it felt like we hadn’t even made a dent on the climb, however, it was starting to make a dent on us. We needed to stop to air our now trench foot-like feet every hour or two—the downside of our plan to only wear our riding gear on the plane. This travel light strategy was really starting to backfire on us as I considered pedalling barefoot for a spell. The fire road was pleasant enough, with a gentle gradient, and the three of us kept each other cheery while reminding each other of previous indiscretions over the past 18 hours. The animals of Whitehorse were clearly taking shelter, wiser than us; our only sighting was a small black bear, jumping out a few hundred metres up the road, glancing at us then deciding he had better things to eat than three smelly, tired, wet humans.

Fortunately, the higher we climbed, the clearer the skies got. The cloud broke as we reached the summit of Grey Mountain. It was 7:30pm when we were gifted our first proper view of the Yukon. The mountain had taken five or so hours to climb from town, but paled in comparison to what lay beyond. Mountains, lakes and the mighty Yukon river stretched as far as the eye could see. It was beautiful. And so was the descent.

Money Shot was the most technically challenging trail yet; steep, rocky and exposed as it descended through the alpine. Again, the descent gave us all a shot of life. All three of us rode like we’d just jumped off a chairlift, passing each other on inside lines and cackling at the trail. This was our first of two descents off Grey Mountain. We’d lost 600 metres on this descent and started climbing to the top for a second time, knowing midnight was getting close.

We knew we had to be at the summit by around 11:30pm. The light was fading and rain clouds were forecast to roll back in. We had ambitiously decided not to pack any riding lights, believing that “of course we won’t need them; it’ll be light the whole time”.

Regardless, we pushed on knowing this would be the final descent of our longest, longest day. We started climbing the final alpine ridge at 10:30pm. The cloudy, murky twilight wasn’t the hours-long beautiful golden hour sunset I had envisioned, but it was still breathtaking. The climb was also breathtaking. By this point, we had climbed well over 3,500m and ridden over 120kms on about 50ish minutes of sleep. The bonk was hitting us all hard.

It was only fitting that this final 1000m plus descent was called “The Dream.” A beauty; blue flow trail, hand-built by volunteers from the local mountain bike club, descended through the alpine back to the Yukon River and into town.

Naturally, we didn’t make the summit quite in time. As we dropped in at 11:45pm, the fading light and cloud made ‘The Dream’ a true and proper dream. Hooting and hollering like the delirious children we were, we scared any wildlife out of the way, the descent once again bringing us all to life. Twenty-four hours in, we were riding like it was lap one; the sandy alpine dirt providing unlimited grip despite the rain. The lights from town steadily got brighter as we got closer, and our grins were ear to ear.

As we rolled back to town at 1am, some 11 hours after we had left from our lunch nap, we realised how hungry and tired we were.

It’s fair to say we had drastically underestimated the logistics. I had planned this trip thinking we’d be riding through the hot summer sunlight, taking rests in fields of alpine wildflowers, and riding all the way through to our flight back on Sunday afternoon. Due to this overly ambitious plan, we had failed to book or bring any accommodation with us. We hadn’t really thought about that until this point, however, food was our number one priority. Whether you are in Whitehorse, Wellington or Warsaw, the golden arches of McDonald’s will always provide. The crispy, salty fries and magic Big Mac sauce filled a void we didn’t know we had.

Considering our options, sitting outside, soaked and bonked, we decided going back to our bike bags under the sheltered porch of the bike shop was our best move. And by god it was. To be honest, we probably could’ve booked a hotel, but we weren’t ready to drag our soaking wet carcasses back to society just yet.

Cozying up in a bike bag might not seem like the comfiest bed to you, if you’re reading this from the couch or the coffee shop, but at 1:30am in the twilight of a rainy Whitehorse morning, it couldn’t have been better.

A successful end to the longest, longest day ride. As the sun properly rose on Sunday morning, we sought shelter in the local coffee shop, promptly falling asleep again, but caffeinated, dry and relatively warm.

We spent Sunday testing out the local BMX track and jumps close to town, then rode back up to the airport, but only after a crucial stop to buy clothes for the flight home. Our strategy of packing only our riding gear had worked out so far, however, by now we were a biohazard. We would not have been allowed to board a commercial flight in the state we were in, so Walmart provided a pair of jandals and enough clothes to let us board the flight home.

Sitting down on the flight back to Vancouver, I felt relieved that the Yukon had let us get away with this atrocious lack of planning. The vastness was real, and a place I cannot wait to revisit with the bike—and perhaps a vehicle and accommodation. Nonetheless, we left feeling successful. We did it, but it wasn’t pretty. We had spent the entire midnight to midnight exploring the outstanding trails, people and town Whitehorse has to offer.