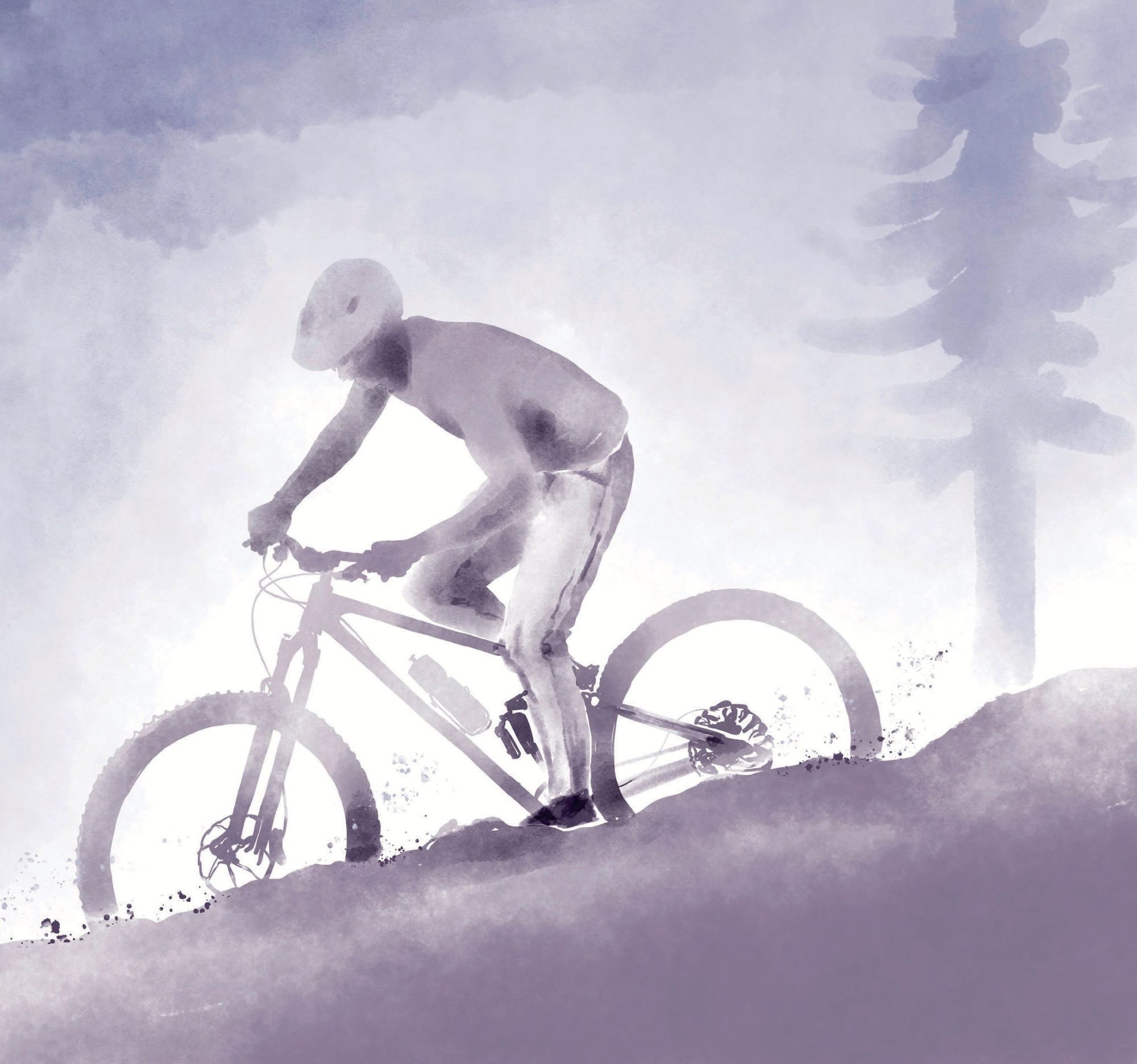

Exposure Therapy

Words Lester Perry

Images Sam Horgan

Each time I head out for a big mission, I’m trying to answer the question: “what else is possible?”; trying to redefine what I can do; and maybe even find a limit to what I can do.

Riding mountain bikes takes on myriad forms. For some, it’s an artistic expression, flowing through trails and jumps, interpreting features in their own way, translating them into a kind of moving work of art. For others, riding bikes is more about the physical feeling: muscles, heart rate, breathing, focus and exhaustion. Some would call it “Type 2 fun”.

My riding life has been expansive: I’ve flowed through jumps, interpreted trail features and chased the clock racing down hills. I still enjoy all aspects of riding but, these days, I’m drawn to bigger and bigger days on the pedals which ideally take in hours of translatable single track.

When I was younger, a three-hour ride seemed impossible but, over time one hour of riding stretched to one and a half, then two, eventually three, then five, then 12. It’s been an evolution over 30 years, and while I’m pushing to find the limits of what my body can do, the more hours I spend pedalling, the more I realise the limits of what I’m capable of are really in my head; mental not physical. It’s a kind of exposure therapy that’s helped me redefine what I’m able to achieve on the bike. Add a bit more time to each mission, more hours, more climbing, more hike-a-bike, a little more of everything. The more we’re exposed to adversity and challenge, the more we can adapt and overcome it.

Generally, when out for a big ‘endurance’ ride, it’s not the body which fails first, but the mind. The mind puts in place safety measures and boundaries to keep our physical self safe, telling us we can’t go further or do more in order to protect us. I’ve found a huge learning is the ability to distinguish between my brain telling me I’m simply uncomfortable, and it telling me I’m actually in trouble, in danger, or perhaps even injured. If I’m sure I’m just uncomfortable and there’s no real threat to my wellbeing, it’s a case of reframing the pain as just information. Information that yes, I’m uncomfortable, but I’m not actually in real danger. Success is about adapting to discomfort and overcoming it in order to keep pushing forward, ignoring the brain saying we can’t, or shouldn’t, be doing what we’re doing.

Big rides bring a big appetite, and food brings comfort when you’re out on the bike for many hours. Food not only provides fuel for our endeavours but helps the brain stay sharp and able to make good decisions. Even having the sharpness to know the difference between being uncomfortable and being at risk. A hunger bonk in the middle of nowhere can be the start of bad decisions and the slide to disaster.

The old saying, “suffering shared is suffering halved” is absolutely applicable here. A multi- day mission seems so much harder alone than when it’s shared with friends. Take the Kahurangi 600 ride I outline elsewhere in this issue; if I’d done that trip by myself, it would have felt like such a huge undertaking with much higher consequences if things went sideways. Sharing the trip with mates made it seem so much more approachable and achievable; much like most things in life.

Each time I head out for a big mission, I’m trying to answer the question: “what else is possible?”. Trying to redefine what I can do, and maybe even find a limit to what I can do. Obviously, it’s a balance between trying to go big and being underprepared, stupidly putting myself at risk, and stepping things up each time, exposing myself over time and taking things up a peg rather than just trying to ride headlong toward a limit to try and break through. That would likely find the limit, but end in tears.

Ultimately, I’m finding that big rides are more than just hours on the bike and kilometres under the tyres. They’ve become a practice in resilience, patience, and redefining what’s possible in other areas of life.

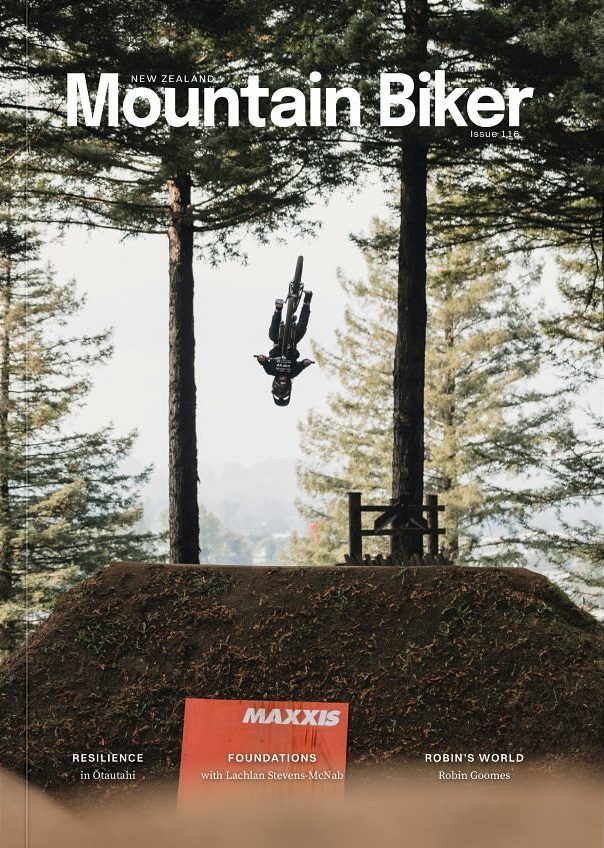

Bike Town

Words & Illustration Gary Sullivan

There are numerous things to note about life in a bike town.

Many you might expect. More bike shops, and better ones, than you would normally see in a regional town. There are many bike-related businesses located in the town for obvious reasons. Distributors. Designers. Skills teachers. Trail builders. In the example I live in, there are even two suspension specialists.

All these activities are here in my hometown because right on the edge of the joint there is a forest full of trails.

What you may not expect, and this is a feature of town that still amuses me after a quarter century of living here, is that almost all professional relationships are with fellow bike riders. And not because they are selected on that basis. The odds are that if a professional chooses to live here, the outdoors will be a big factor in the reasons why. And, if you are going to be an outdoors person around here, there is a solid chance you will be some sort of mountain biker. So, it follows that many contacts in the day-to- day are also likely to be seen out in the trails.

The first professional I encountered when we moved here, while we were still living on and off in a campground, was a doctor. I went to see her because I had munted my shoulder by going over the bars and had the extreme good fortune to get an appointment with a woman who has become a great friend. I knew she was likely to be a great doctor when she listened to my tale of woe then said, “that isn’t so bad, check this out” and proceeded to pull her shirt aside so the row of screws in her clavicle popped up in clear relief. She had busted herself mountain biking. For the 27 years since then, we have compared notes about our rides every time I have needed medical care.

In that time, I have also become acquainted with accountants, bankers, lawyers and physiotherapists, all of whom are dead keen mountain bikers.

Not to mention the nurse, the radiologist, the aneasthetist, and the emergency department doctor who dealt with me on one incredible visit to the hospital. All mountain bikers. My get-up made it obvious what I had been doing to snap my clavicle, but the novelty was talking to a series of people who wanted to know which trail, and where on the trail, and oh yes, that bit. They knew exactly where I had binned it.

The latest example of this trend is another medical professional.

When I got on her roster she had just moved here. When we met, we discussed the marvels of the forest, among other aspects of her new hometown.

She reckoned she loved the forest but couldn’t imagine going in there on a bike – too dangerous.

I only get to see her once or twice a year. Around the time of our second or third appointment, it turned out that bikes were now on the agenda, and she was riding a few of the forestry roads with her crew and really enjoying them.

The next time the Forest Loop was the favourite.

On my latest checkup, I learned that they had moved on to full suspension bikes, and were loving Grade 3 trails, like really fizzing about a couple of them.

It is currently pollen season, and she has really bad hay fever. She reckoned if she had known how bad the pine pollen was, she might never have moved here.

But, with those trails right next door, there is no way she would move away now!

Metronomic Meditation

Words & Image Gary Sullivan

“It gots to be accepted;

That what? That life is hectic.”

C.R.E.A.M. by Wu-Tang Clan

Although they’re all credited with writing their legendary song, C.R.E.A.M., I’m pretty sure it didn’t take all of the Wu-Tang Clan’s nine iconic members to write that lyric from their debut 1993 album. Whether they all pitched in, heads bobbing as they gathered around a smoking ashtray, behind a mixing desk, or if it were just a single MC with a pencil and notebook scratching notes while on a grimy subway, one thing is for sure: there was one purpose. Whether a posse of nine or an army of one, single-mindedness helped create the masterpiece, confirming we need to accept that, indeed, “life is hectic”.

It’s how we deal with our hectic lives that matters.

And there are many ways to deal with how hectic life has become recently. For most, it’s a combination of different things that take their mind off the busyness of life; for others, it’s singlemindedness, or a single act, that calms them, enabling a refocusing of the mind—away from the stressors of daily life. If you’re reading this magazine, I’m sure that—for you—one of these things is probably mountain biking; a single-minded act. I know for me, personally, at times, riding is more than just a sport; more than just an activity to fill a couple of hours. It’s a meditation of sorts: a metronomic meditation.

Metronomic meditation. I didn’t come up with this phrase but, when I first heard it, it struck a chord. Meditation is “a practice that involves focusing or clearing your mind using a combination of mental and physical techniques”. Both are things that mountain biking requires. Particularly on a technical descent or fast-but-flat singletrack, focus is paramount. I can think of countless times where, had I not been 100% focused on the task at hand, I’d be down a bank, over the bars, or have slid out on an ice-like, wet clay surface. That need for focus means clearing my mind of clutter and forgetting the day-to-day. There’s no space for thoughts other than those required to keep the ship upright, and should my mind wander back to ‘normal life’ even just a little, the consequences could be painful.

Several factors add the metronome-like aspect to mountain biking. Firstly, the pedalling. Stop pedalling while on the flat or going uphill and we fall over; it’s pretty simple. If we’re out for a big day on the bike, the metronome- like effect of pedalling can last hours with only a marginal variation of cadence. It’s simple to ignore, but we’re often pedalling 80 times a minute—multiply that by three hours and 14,400 rotations, which is no doubt metronomic. Then there’s the metronome of our breathing, which is directly related to our pedalling cadence and power. Both affect our breathing, how deep it is, and its frequency.

Boil it all down and it’s pretty basic, really. Between our 100% focus on the trail and the subconscious metronome of our cadence and breathing, we can slip into a trancelike state. Now I think about it, some might call this the ‘Flow State’, but for me, ‘Metronomic Meditation’ is equally adept because we essentially remove ourselves from reality and are forced to cleanse our mind of the day-to-day—a ‘mind bath’ perhaps.

As much as I’m a mountain biker at heart, I spend a lot of time on my local roads, asphalt or gravel. This riding ticks the sporting and physical aspects of riding for me, but I find it’s only partially metronomic meditation. Roads are wide, and I don’t need to pick a cautious line between obstacles or weight my pedals just right across an off-cambered section. I can just concentrate purely on pedalling and staying on my side of the six-inch wide white line, still able to contemplate my daily problems and figure out what I’m having for dinner. There’s undoubtedly some metronomic pedalling and breathing happening, but it’s hardly meditation.

Life is hectic. It’s fair to say, at least for me, mountain biking is the truest form of single- minded metronomic meditation that eases that hecticness (is that even a word?!), if even just for a few hours a week.

Give it time

Words Lester Perry

Image Henry Jaine

Some bikes are ridden so often, and in so many moments and places, that to part with them becomes almost impossible.

They develop value to the owner which has no connection to reality, so selling them is not only unsatisfactory from a financial perspective, but an emotional wrench that can be too difficult to execute.

Same goes with cars.

Our relationship with our vehicle is kind of like the way we treat drivetrains. There are essentially two ways to do that: keep it fresh by replacing the chain every thousand kilometres; keep an eye on the chainrings and replace them when necessary—and hope that doing those things will make the cassette last longer than it may otherwise. Or the other way, which is ride the stuff until it more or less dissolves, then replace the lot in one mad spend-up after a couple of years.

The more traditional among us get a nice set of wheels when they are able, then trade in or up as often as once every couple of years. The alternative lot buy a vehicle that ticks the required boxes and drive it until it dies—or they do.

That has been my style and, so far, I have outlived half a dozen of them—not counting the odd ones I owned briefly in my youth, and the more sensible ones I have shared with my partner.

The last three have been Toyota HiAces. These venerable buses are examples of what I would argue is the Kombi of the South Pacific. These days, actual Kombis are like high end bicycles: their price bears no relation to their functionality. Don’t get me wrong, they are cool things. In their primitive way they will still be clattering along when cockroaches inherit the planet. But, for everyday abuse and long- lived up-for-itness, the HiAce is hard to beat.

Also hard to kill.

The late 80s white example we caned for a decade, had a slipping clutch for at least five years, which Glen used to repair using positive thinking. Just when we thought it wasn’t going to get whatever pile of stuff we’d loaded into it to the top of the next hill, she would send it kind thoughts and it would take another deep breath and soldier on. Some dear friends took it off our hands and toured the country in it, before selling it to a wrecker in Christchurch.

The one I almost wear as a totem is called a Regius, but it is a HiAce at heart. Sidebar: I reckon a good career, if I was a younger man, would be as a consultant to Japanese car companies, helping them to avoid coming up with names like ‘Regius’. And HiAce for that matter. But, I digress. I have heard this model referred to as a “Loser Cruiser”, but it has carted me, my partner, numerous bikes, a kayak, and a caravan over a quarter of a million kilometres around our country and still goes like it did when I got it.

I have just replaced it. I decided that if I get a decent HiAce now, it will probably be the one that stays on the road longer than I do. I took delivery of it last week, and told a friend about it that evening. I honestly thought she was going to cry. In her view, the old van is part of me. “Surely you can’t be going to sell it!” she exclaimed.

Well, that is the plan.

That was the plan. Now? I am not so sure. Yes, yes, I am. Out it goes.

So what’s the attraction for me, in a HiAce? Mainly; that it’s a van. You can drive around in it. You can keep a bike in it. You can get changed in it, take a nap in it, take shelter in it. You can cart a collection of bikes and people, a pile of rubbish, or half a house load of furniture. You can go camping in it—at a pinch, you could live in it. We have done all these things and more.

I prefer to get one that is past the number of kilometres travelled where problems would have cropped up if they were going to. It is best if the thing already has dents and scratches in the usual places. That means any imperfections I add to it will be pleasant memories of tight spots or straight fuckups, not heartbreaking blights on what was a virgin body.

The new one (well, new to me) has very little personality. Personality will develop, as bits of bark get scrubbed off the corners, bicycle tyre marks get added to the interior, kilometres get added to the clock and resale value slowly becomes irrelevant because with any luck I will never sell it.

Like one of my road bikes, it will become so valuable to me, it will be more or less priceless.

Give it time.

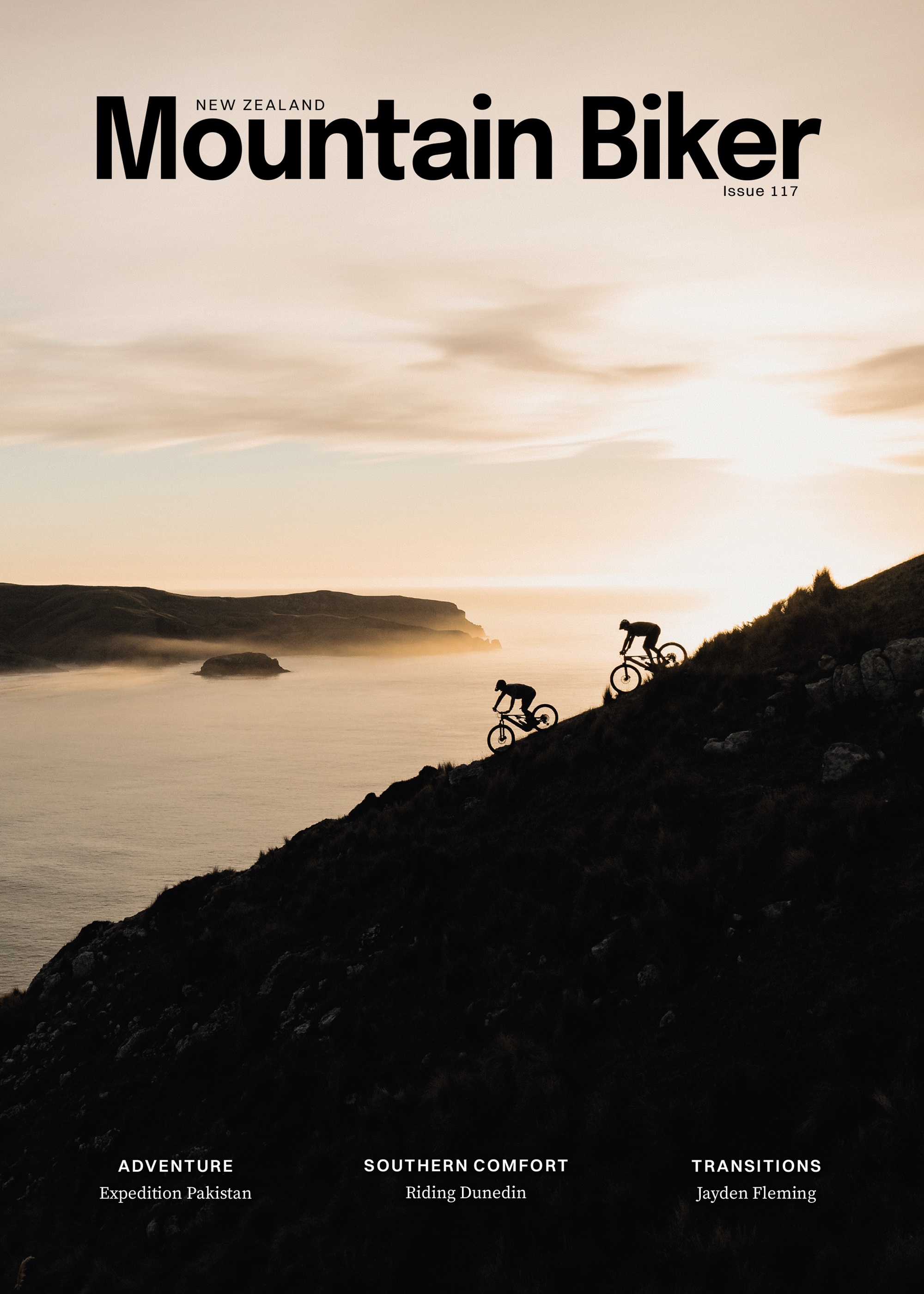

A grown man’s Disneyland

Words & Images Lester Perry

When I was a kid, I saw Disneyland, in California, as a mythical place that only a privileged few kids from my school ever visited. The tales they returned with further increased the mystique of the place. Interestingly, it wasn’t ever a place I thought I would visit myself and, to this day, I still haven’t.

As I grew up, the appeal of Disneyland waned, as you’d expect, and my “Disneylands” soon became famed spots around the globe where I’d dream of riding my bike. By the early 2000’s, Whistler Bike Park had secured its spot near the top of my list of places I dreamed of visiting.

For so many reasons, none very good really, it would take another 22 years before I was finally in a plane, jetting my way to explore British Columbia for the first time; two weeks in an almost-clapped-out van, just me and a mate. A whirlwind trip through western BC started with a quick bump into Bellingham, a trip back through too many riding spots, and finished with a scant 24 hours in Whistler. This gave me a taste of what the place was about, with a few laps on the chair and an early morning Dark Crystal lap. I knew I’d need to return in the future to delve deeper into its trail network.

By early 2024, the itch to travel to ride was back—and this time, I had a larger crew. Three middle-aged dudes—Kai, Byron, and myself— and 12-year-old Myles, Byron’s son. We knew we wanted to ride abroad; a trip that would be not- too-punishing (on bodies and budget). So, a direct flight from Auckland to Vancouver was chosen. From Vancouver to Whistler, there are a few transport options, but a shuttle did the trick for us, dropping us off at the door of our accommodation. If you were keen, you could leave Auckland, take a nap on the plane, wake up in Vancouver, shuttle to Whistler, and be on the chairlift for afternoon laps.

A ten-day lift pass, the cheapest apartment we could find just a five minute ride from the main lift, and a red hot credit card: game on. Our plan was simple; ride pedal-accessed trails in the morning, then lap the park and trails accessed by the lift in the afternoon and into the evening for ten consecutive days. No days off.

Whistler has around 14,000 permanent residents, with an additional 2,000 odd seasonal residents, however, it gets a whooping three million visitors a year, 55% of whom visit in summer. That’s a lot of mountain bikers, you may think, but only around 100,000 of them visit to ride, and I’d wager a pretty hefty bet that the majority of them never make it out of the bike park.

The bike park in Whistler is awesome, with trails of all types and for all styles. There’s no need for me to go on, as you’ll have seen many of them on the internet. What’s less well-publicised (but still popular with a large number of riders) is the pedal-accessed trails. We only managed to scratch the surface of what’s in the valley outside of the bike park, but the taste we got only re-confirmed Whistler as a 1-stop shop for everything mountain biking. Every morning, we pedalled to a new trail and not once struck a dud.

Jump onto Trailforks, and you’ll see a good web of trails down both sides of the valley. View a heat map of the area, and you’ll find a few more but, ride with a local and there’s a whole other underground network of must-do trails. The kicker is you’re pedalling to get to them, and they’re purposely made difficult to get to.

With some unseasonably wet and grim weather at play for much of our trip, the high alpine pedal-accessed trails we wanted to target were off-limits. Although the trails in the area handle the rain exceptionally well, low clouds and cold temps up high put us off some of the marathon climbs. The lower valley and bike park trails were key in these scenarios.

Although we missed a few missions due to weather, we managed just enough clear weather to make the most of a Top Of The World uplift. We rode the upper section before dropping into Million Dollar, Four Eyes, Kashmir and Kush, eventually dropping our pumped arms down into Creekside for refreshments. This is living, Barry.

If you’re into a bit of racing, Phat Wednesday is a must-do. A weekly social gravity race that is the price of a beer to enter, and you get a free beer at the finish—I guess that’s basically a net gain?

Kai and I hit the race in heinous conditions and still had a great time; the Whistler dirt, although muddy, wasn’t that slippery, and we had a blast regardless. The riding community there is next level.

Getting around Whistler is simple—just jump on the extensive bike paths and meander your way to your destination. It’s a simple way to get around and a great way to access the valley trails or tie in some touristing while you’re cruising around and hit the lake for some bombs off the jetty.

Having a bit of time, a trip to the Whistler Train Wreck was in order. One wet morning, we rolled out to it for a look. Riding from the village, we explored flatter trails off the sides of the bike path, riding some fun old-school hand-built trails that would easily be overlooked had we not gone full tourist mode. The Train Wreck spot has been featured in quite a few MTB movies over the years, so it was cool to see it in the flesh. Our ride home featured more exploring, and we stumbled upon a zone full of ‘skinnies’. Scary and exciting at the same time, I relived my youth for a bit, but after almost getting out of my depth a couple of times, I wised up and moved on.

Whistler trails can be humbling. The level of some trails is so high we really wondered if anyone would ride them—the consequences are so high. But, as much as there are some super gnarly trails and features, it’s not a rule; there are plenty of fun intermediate and advanced trails that were enough to test our limits without putting ourselves at too much risk. I guess a key thing when travelling abroad to ride is knowing your limits and being happy to swallow your pride, dismount and walk a section if there’s any doubt you’ll make it through. We saw plenty of people wandering the village with arms in slings or legs in casts. There’d be nothing worse than being on the opposite side of the globe, injured and unable to ride.

During a day in the bike park, you come across all facets of the MTB world. From first-timers protected beneath layers of rented body armour to new-school, roll-cuff-Dickies-pants and tee wearing, full-time park rats. It really is a melting pot for the world’s mountain bikers. While the ANZAC contingent is strong, there are accents from all over the world, and groups flock there to ride from all corners of the globe. It’s pretty cool to see one sport pulling so many people to one place.

Common bonds run deep in the riding community, and it was great to reconnect with people I’ve met through riding over the years who now call Whistler home (permanent or temporary); to be shown some of their adopted backyards and get a local lens on where to find not only the best riding, but the best coffee, or best value meals in town, or even a loan vehicle. If it weren’t for the connection the bike brings, chances are a trip to the area would be nowhere near as rich; it’s more than just a place to visit and ride to me.

I could wax on for pages about why Whistler is worth a visit, but I think you get the idea. With a direct flight (ex Auckland) to Vancouver cheaper than to anywhere else worth riding (aside from Tasmania), although it is overall not a cheap exercise, a 10-day trip offers insane value for money: the sheer number of riding experiences on offer once in Whistler is unparalleled. Assemble a crew, watch for cheap air tickets and go! YOLO.

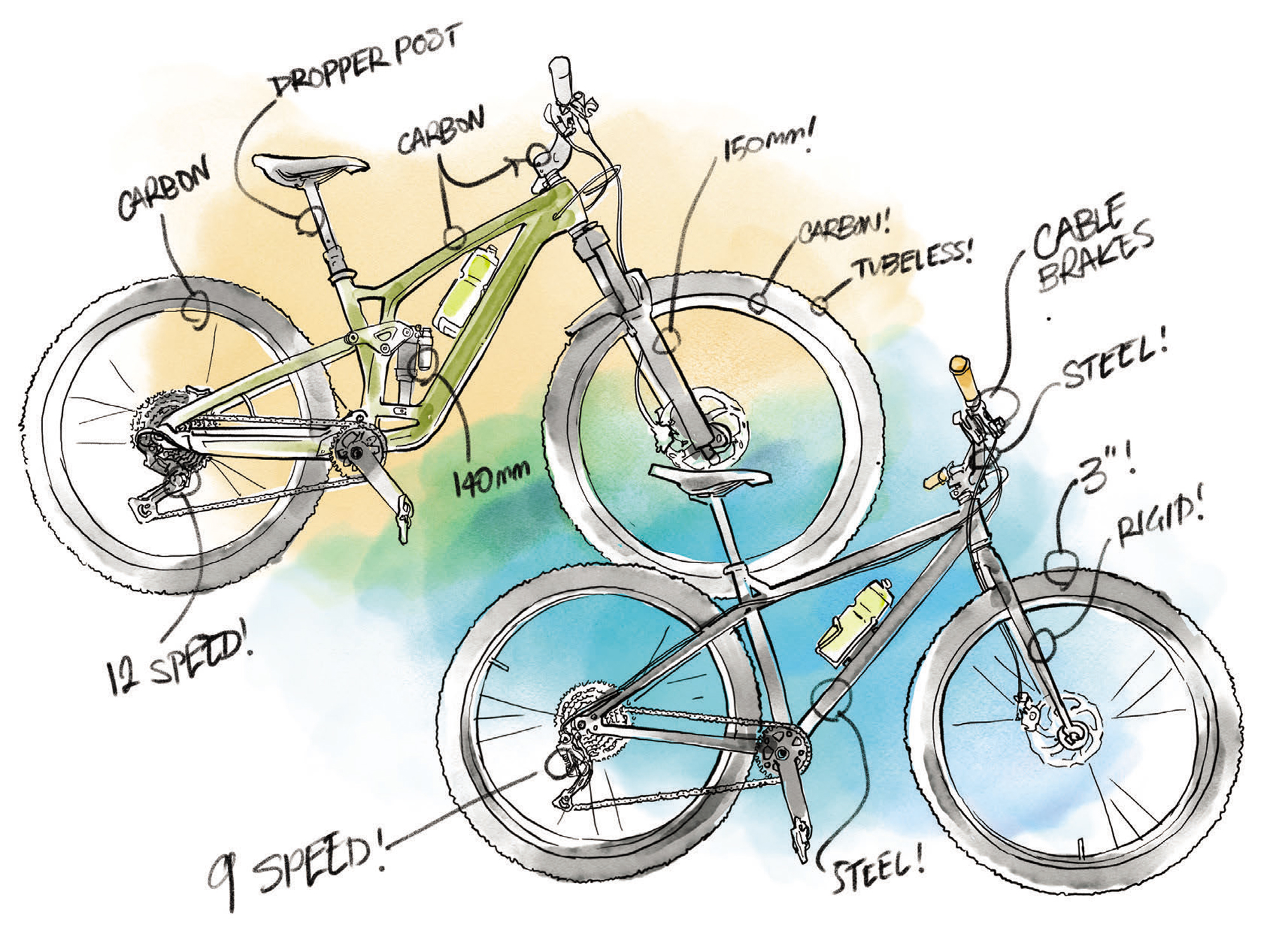

It’s not about the bike

Words & llustration Gary Sullivan

This week I completed an experiment. It wasn’t scientific and it proves nothing, yet I still think the result is worth sharing.

The weather has been iffy. In the first instalment of the experiment, I rode a thing called the Forest Loop on my Surly Krampus.

The Forest Loop is a thing that has been developed in my home town of Rotorua which gives more or less anybody a decent serve of the splendours of the location without being particularly challenging. It is what we call Grade 2 which, around here, means a metre wide path with very few roots or rocks, no drop-offs or anything very steep, and pretty well weather proof. It provides a nice view of three lakes, a variety of forest and 34 kilometres of rolling trail. There are countless ways to adjust the route for personal preference, but the official version is very well signposted so it would be difficult to get lost. It serves two useful purposes for me. Firstly, any newcomers to town who want a ride, can be sent on it. Before the Forest Loop, it was almost impossible to send an initiate into the woods without a guide. Maps are useful, but Whakarewarewa is a complex place. Now, it is simple – just follow the signs. The second benefit for me, is that it provides a good outing when it’s too wet to go into the rest of the trails.

When it’s raining, but I want to rack up some kilometres, the Forest Loop is a good, tried and true choice.

The Krampus is a machine I acquired to do a long bike packing tour on, which, for various lame reasons has not yet happened. Meanwhile, the bike is fun for some applications, on certain days. It’s the original version of a concept Surly more or less invented, 29+. The wheels are 29 inch, and carry three inch tyres.

No suspension, simple and inexpensive running gear, no dropper post, not that much to wear out or worry about. I have added and subtracted a few things over the years but, currently, it sports some bars which are very wide, have a lot of rise, and a cross brace like an old school motocross example.

Once again, when it’s raining but I want to rack up some kilometres, it’s a good choice.

Mostly out of habit, I started my GPS recording device and beetled off up the first climb.

It turned out to be a pretty decent day; the rain was light and stopped a few times, and there was even a brief appearance from the sun.

My route ended up following the Forest Loop until the last section, which is a boring concrete path down the side of the highway. I took a bit of singletrack and a couple of forestry roads to stay on dirt, in the trees. To my surprise, I got back to the van in a hair over two hours. That represents an average speed of 17kph. That’s a good chunk faster than my usual mountain bike ride, but I figured that was because my usual rides involve going up several long, steep climbs where I am going so slow that my GPS device sometimes pauses because it thinks I am stationary. The Forest Loop has a total of 600-odd metres of climbing, but it is never very steep – and is widely distributed over 34km. Still, pretty fast by my standards.

That’s why, a couple of weeks later, I decided to take the same route; this time aboard my late model, comparatively sophisticated, trail bike.

I tried to emulate all the variables. It was a fairly crappy day, but maybe a bit nicer than the first example. Breakfast was matched exactly, coffees calibrated to be of equal quantities and strength. Same outfit, different print on the cotton T.

My ride was very nice, although I confess I was maybe trying a bit harder: the first outing didn’t become part of any performance experiment until after it was completed. This time, I knew there was a sort of race on.

I got back to the van in a time that was faster than the first one. By a minute. Well, a minute and 13 seconds if you want the details. Heart rate, a measurement I sometimes wish I didn’t know about, was fairly evenly matched, and top speed showed only 2kph of difference.

OK, there are dozens of places in the woods I wouldn’t even try to ride on the Krampus that are fun and light work for the Fuel. But still, I’m amazed by how two rides that felt so utterly different to complete were more or less the same in terms of how long they took.

Big Timber: Where would we be without it?

Words Lester Perry

Image Cameron Mackenzie

Once upon a time, Aotearoa was covered mainly by a blanket of native bush. You know the stuff? It’s what most mountain bikers love to ride: large trunks, matts of roots dispersed with fertile dirt, and leaf litter (Beech leaves if you’re lucky).

And this bush was the habitat of many native NZ species. Early Maori cleared what land they needed for agriculture and living space, but it wasn’t until European settlers came ashore in the early 1800s that the axes really got swinging. In the space of roughly 200 years, we (humans as a whole) have cleared a fair chunk of NZ’s land mass, leaving just 24% of it covered in native bush. Forty percent of this lump of land we call home is now pastoral farmland, and 6% is commercial forest, which is also home to a large percentage of NZ’s mountain bike trails. As sustainable as commercial forestry operations now aim to be, there’s no denying that this – combined with pastoral farming – has altered NZ’s ecosystem permanently.

While driving the black band of road that dissects farmland throughout this fine country, I often wonder: what would NZ be like if it were still fully forested and, more specifically, what would mountain biking be like if it were?

Anyone who’s spent time on the end of a spade digging a trail in the native bush would agree it’s hard graft, and working the earth through native bush with a digger is a chore requiring time-consuming finesse and, unless you’re comfortable destroying native roots and eco- systems, then it’s all but impossible. With diggers off the trail builder’s menu when they’re working in native, the speed of trail building would be slow, and the extensive networks we currently see would be a figment of imagination.

If, theoretically, all our trails were in native bush – and given the time necessary to build them by hand – the cost of a build would render them basically out of reach financially, and trail building companies, of which NZ has a number, would be almost non-existent. A lack of professional builders would mean volunteer builds would rule. Lord knows how difficult it is to get a regular crew of keen volunteers to commit to a build under the canopy of pines, let alone the challenges native bush brings.

Native trails are my favourites; their environment and the fact they’re generally hand built give them an inherited technicality and often unique style of flow. It would be amazing to be riding native trails every time we went for a ride. Digger-built flow trails – be gone!

I’m not a hater, though; pine plantation trail networks have enabled NZ’s MTB scene and industry to boom, thanks to their accessible, well-groomed, quickly-built trails. The trail is less directed by the lay of the land or preservation of native trees and more by wherever the digger driver points their machine. With only a small number of roots to dodge, or undergrowth to clear, these trails come easy. On many trails, pine needles help protect the surface through winter and, come spring, a leaf blower and a rake can help rejuvenate much of the trail surface. No one likes losing their favourite trail to logging. Still, with commercial forests running on a 25 – 35 year logging cycle (usually the shorter), it’s inevitable that at some point, one of your favourites will be gone. Once trees are felled, there’s a relatively clean canvas to work on, the opportunity for new trails, and the commercial operations that usually build them. But let’s not forget all the logging slash that’s caused significant problems in the last few years, or that trails built in clear fell generally take much more upkeep and are often terrible to ride due to erosion through a wet winter.

Although I’d love to see a country blanketed in native bush again, I can’t imagine NZ would be such a mountain bike mecca if it was. It’s a little Yin and Yang but, ultimately, big timber will continue to thrive with or without MTB trails. I fear that, without it, the growth and popularity of MTB trails in NZ would be stifled, and we wouldn’t be the global destination we are.